The Columbine Mine Massacre

Introduction

As a society we seek to hold life sacred. Our laws contemplate capital punishment for transgressors against this trust. Beyond anger at violence that disrupts the social order, beyond revulsion at the deed or sympathy for families of victims, we recognize implicitly that our loved ones might have been in the line of fire.

IWW Prose

The Columbine Mine Massacre

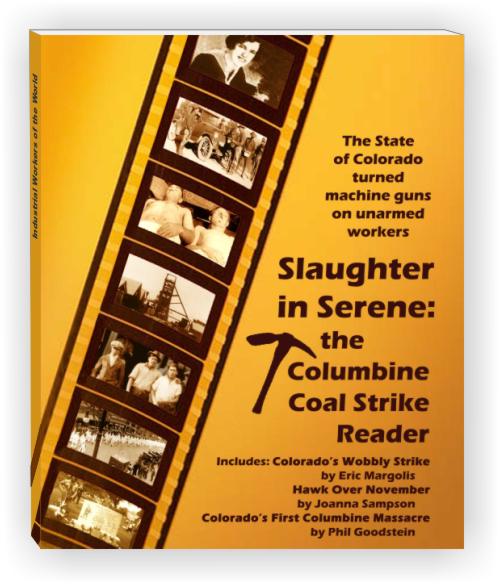

Available now— Slaughter in Serene: the Columbine Coal Strike Reader! It matters little whether the deed was recent, as in the killings at Columbine High School, or years ago, as in the killings at the Columbine Mine in Serene, Colorado. Our fascination and our horror remain focused upon the question: how can the killers be so calloused, so uncaring, so different from us— that they might commit atrocities against fellow humans? Beyond simply coming to terms, remembering and understanding such motivations and deeds might help us to guide our beliefs, formulate our laws, and teach our children to deal with dangerous circumstances. The murders at Columbine High School shocked us in their barbarity. We must remember. But our shock is also a measure of how society has changed. The murders at the Columbine Mine in 1927 were horrific. Yet sadly, they shocked only a few. There is one other important difference. The 1927 murders were recklessly perpetrated by a police force in the pay of the governor of the state of Colorado. The machine gunning of striking coal miners was orchestrated by a small but powerful segment of the business community and was encouraged by lurid editorials against immigrant workers in Colorado's daily papers. The citizens of Lafayette burned those papers in the street as a sign of their agony and their sense of betrayal. Lafayette wanted justice; Denver simply wanted coal.

The COLUMBINE MINE MASSACRE

North of Denver there is a quiet hilltop with a pleasant view of the surrounding plains. Birds flit through the trees and honeybees buzz about the wildflowers along Highway Seven and Interstate 25. There is a small parking area from which a traveler may take in the tranquil view.

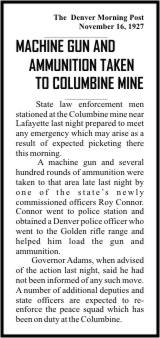

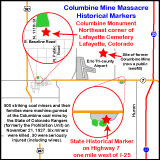

It was a chill November morning in Serene, home of the mighty Columbine mine that was nestled peacefully on a rolling Colorado hillside. The strike was five weeks old and strikers had been conducting morning rallies at Serene for two weeks, for the Columbine was one of the few major coal mines to remain in operation. Five hundred miners, some accompanied by their wives and children, arrived at the north gate just before dawn. They carried three American flags. At the direction of Josephine Roche, daughter of the recently deceased owner of Rocky Mountain Fuel Company, the picketers had been served coffee and donuts on previous mornings. This morning men with guns would serve up something different. Denver Post demanded military action Serene was surrounded by two fences and the strikers were met at the outer gate by Weld County Deputy Sheriffs Louis Beynon of Frederick and William Wyatt of Greeley. Beynon warned the strikers not to enter the Columbine property, not to push their luck on this particular day. He tossed a few dollars worth of coins onto the ground saying that's all I have, please take it and go home. Some of the miners scrambled for the coins. Others argued that Serene had a public post office—and some of their children attended the Columbine school—so they had a right to continue holding strike rallies there. Wyatt claimed that the strike issues would probably be settled by the following Friday. In the words of Mrs. George Kubic, wife of a striking miner from the Shamrock mine, "He told us the same thing before, however, and we decided to go on in. There was no mention of staying out in the name of the law. We were not armed and we did not expect a thing in the way of trouble." The deputies drove their two cars to the inner gate where they were admitted onto company property, and the strikers followed. The Columbine Mine Massacre Highway Marker Beyond the gate the miners were surprised to see a detachment of state police dressed in civilian clothes but armed with automatic pistols, rifles, riot guns and tear gas grenades. The rangers were backed up by rifle- toting mine guards stationed on the mine dump. Head of the rangers Louis Scherf shouted to the strikers, "Who are your leaders?" "We're all leaders!" came the reply. Scherf announced the strikers would not be allowed into the town, and for a few moments they hesitated outside the fence. There was discussion, with many of the strikers asserting their right to proceed. One of the state police taunted, "If you want to come in here, come ahead, but we'll carry you out." Longtime Lafayette resident Lewis Starkey, then a miner from Erie, recalled later that he thought it was a bluff. Times-Call Article On The Columbine Massacre More taunts were exchanged. Popular strike leader Adam Bell stepped forward and asked that the gate be unlocked. As he put his hand on the gate one of the rangers struck him with a club. A sixteen-year-old boy stood nearby holding one of the flags. The banner was snatched from him, and in the tug-of-war that followed the flagpole broke over the fence. The miners rushed toward the gate, and suddenly the air was filled with tear gas launched by the police. A tear gas grenade hit Mrs. Kubic in the back as she tried to get away. Some of the rangers hurled rocks and clubs and the miners threw them back. The miners in the front of the group scaled the gate, led by Adam Bell's call of "Come on!" Bell was pulled down by three policemen. Viciously clubbed on the head, he fell unconscious to the ground. A battle raged over his prostrate form, the miners shielding him from the rangers. Mrs. Elizabeth Beranek, mother of 16 children and one of the flag-bearers, tried to protect him by thrusting her flag in front of his attackers. The police turned on her, bruising her severely (police admitted to using clubs in the skirmish. In Scherf's words, "We knocked them down as fast as they came over the gate"). Rangers seized Mrs. Beranek's flag too. A striker belted one ranger in the face, breaking his nose. Blood gushed from a cut above one ranger's eye when a rock found its mark. The police retreated. Emboldened by the retreating police, strikers forced their way through the wooden gate, shattering the padlock. Jerry Davis of Frederick held his flag high as hundreds of angry miners surged through the entrance. Others scaled the fence east of the gate. The police formed two lines at the water tank a hundred and twenty yards inside the fence. Louis Scherf fired two .45 caliber rounds over the heads of the strikers. His men responded with deadly fire directly into the crowd. In the early dawn light the miners scattered under a hail of lead. Twelve remained on the ground, some writhing in agony while others lay still. Three machine-guns had been installed at the mine and miners later claimed their ranks were decimated by a withering crossfire from the mine tipple— a structure where coal was loaded onto railroad cars— and from a gun on a truck near the water tank. John Eastenes, 34, of Lafayette, married and father of six children, died instantly. Nick Spanudakhis, 34, Lafayette, lived only a few minutes. Frank Kovich of Erie, Rene Jacques, 26, of Louisville and 21 year old Jerry Davis died hours later in the hospital. The American flag Davis carried was riddled with seventeen bullet holes and stained with blood. Mike Vidovich of Erie, 35, died a week later of his injuries. Denver Post Article On The Columbine Commemoration There were three-score wounded, twenty-five of whom were identified in the press. They were from Broomfield, Superior, Longmont, Marshall, Canfield. At least two women were badly hurt. Fortunately many of the area children were in school. The daily papers were filled with false accusations by the state police. Miners were said to be armed with sniper rifles, pistols, even bottles filled with nitro-glycerin slung on ropes under their coats. Later analysis of a sample "nitro-glycerin bomb" by the state oil inspector determined that it was filled with tear gas. Some police claimed sharpshooters had been sniping at them all morning, even prior to the meeting with Beynon and Wyatt outside the gate. Reporters naively filed uncritical stories from the police who pointed at the bullet holes on the outside of the wooden gate, citing them as proof that the miners had fired weapons—this in spite of the fact that the miners were pouring through the gate when the shooting started, and Scherf's statements make it clear the gate had swung open. Several employees of the Columbine also claimed that the miners were firing weapons. No policeman was shot. Marshal Will Lawley of nearby Erie told the Rocky Mountain News, "I was in the crowd at the mine gates and know positively that the men were not armed." Deputy Wyatt testified at the coroner's inquest that he did not hear any shots from the miners. The miners recall that Adam Bell sternly insisted all weapons must be checked in at the strikers' meeting place in Erie each morning. Two Weeks Before The Massacre... Press accounts focused on whether machine-guns were used, along with repeated police denials. One witness described .30 caliber machine-gun bullets striking the ground like a plow overturning the earth. The Denver Post stated, "strikers dropped like grain before a sickle... the dead and wounded began falling and the screams of the injured rose above the pop, pop of pistol shots..." Two days after the incident the Rocky Mountain News printed a photo of the machine-gun mounted high on the Columbine tipple, ready for action "in the event of further trouble". Five Days Before The Massacre... Newspapers printed a statement from an uncomfortable Governor Adams that the machine-guns were mounted before and after, but not during the shooting, at which time they had been placed in storage at his personal request. Citizens of Lafayette were so enraged at what they described as lies in the press that they burned stacks of newly-delivered newspapers in the street. The state ranger unit (the former dry unit from prohibition days) had been specifically constituted on November 4 to deal with the coal strike. On November 7 Scherf executed a midnight raid in Walsenberg, arresting strike leaders. There is much anecdotal and some circumstantial evidence that the police planned an ambush at Columbine. They had called for delivery of helmets and bayonets that morning. According to the Rocky Mountain News the adjutant general of the Colorado National Guard (Newlon), four National Guard lieutenants and two majors, advisor to the Governor (Lacy) and the Chairman of the State Industrial Commission (Annear) were "by chance" at the Columbine mine to witness the shooting. Writer Joseph Conlin states that Frank Thurman, operator of the Black Diamond mine near the Columbine confirmed in 1976 that "the (coal mine) operators had conspired over the weekend to attack the miners on Monday, November 21". The Weld County Sheriff and six deputies also were there but did not take part. A group of Greeley area businessmen was appointed to assess responsibility for the bloodshed, and they laid the blame squarely on the workers. Boulder coroner E.A. Howe stated, "I know the cause of death without any inquest." He marked the death certificates, "gunshot wound incurred in a riot at the Columbine Mine." The state police had already arrested and jailed the strike leaders, charging them with responsibility for the deaths. The National Guard was sent to the coal fields in full battle regalia, supported by tanks and Douglas Bomber aircraft. The fence at the Columbine was illuminated with floodlights and electrified to 420 volts. Two union halls were wrecked by "citizen's committees". A likely motive for the attack is reflected in a Denver Post editorial, "Now that the National Guard has been sent into the field, Colorado looks to an early termination of the coal strike...Colorado must have coal." Rocky Mountain Fuel, the company that operated the Columbine Mine had a good record of labor relations after the incident. Josephine Roche was in the process of taking control of the company when the violence occurred and she was unaware that other coal mine operators had sent the rangers to the Columbine. Governor Adams was quoted on the day of the incident by the Rocky Mountain News, "The situation developed as a distinct surprise to me as no later than last night the officers of the company owning the Columbine mine not only stated that troops were not needed, but that they were not desired". In a 1944 memorandum Miss Roche identified Jesse Welborn, John D. Rockefeller's lieutenant in Colorado, as primarily responsible for the dispatch of the rangers. John Eastenes, father of six children, was first to die and first to be buried. The Wednesday funeral saw Union Theatre in Lafayette packed to capacity. When the Reverend Mr. Boner, Methodist minister, raised his hand for silence the subdued murmuring of the miners and their families ceased, broken only by the stifled sobbing of Mrs. Eastenes and her six children. Then the simple strains of "Lead Kindly Light" sung by a quartet of four miners filled the room. When the last notes of the old hymn had been sung the Reverend Mr. Boner talked of how Eastenes died. "He died a martyr to a great movement," he said. "He went to his death just as other martyrs of history have died for their cause". Pictures From the Columbine Mine Massacre Memorial Service On Thursday Nick Spanudakhis was buried in a ceremony that was a blend of rituals of ancient Greece and pioneer America. Miners from all over the state were arriving in Lafayette to pay their respects. Three thousand attended. One relative, a cousin from Walsenburg sat alone, silent, in the front row. It was Thanksgiving Day. On Friday Jerry Davis and Frank Kovich were laid to rest. The crowd of five thousand was overflowing. Rene Jacques was buried on Saturday in the family plot in Louisville. His aged parents watched the last of their line consigned to the grave. The Columbine Mine Massacre Monument 360° Panorama View From The Monument Scherf's men were later involved in killings in the southern coal fields. In 1927 picketing in any form was illegal. The mine operators, their hired guns and the hostile newspapers made use of crude racist stereo- typing and slander to undercut public support for the strike. Rather than industrial revolution, Colorado was experiencing industrial feudalism. The miners were routinely cheated out of a fair wage by rigged scales, payment in scrip, grossly unfair credit schemes at the company store. Spending on mine safety was so lax that the rate of death in Colorado coal mines was the highest in the nation. By such injustices did the industrial tycoons amass their fortunes. After the strike ended the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company shocked the other mine operators by going on record claiming that the working conditions were the cause of the strike, rather than the workers' union. The Columbine miners became so supportive of the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company that they voted to loan part of their increase in wages back to the company when the other operators tried to drive it out of business. Eventually the coal operations were closed down, and much of the stock was turned over to the United Mine Workers. Thus ended one of the most fascinating—and in some ways tragic—chapters in Colorado history. For sixty-one years the graves of those killed in the strike were unmarked. A recently installed historical marker recalls the Columbine mine and the massacre on Highway Seven, one mile west of I-25. Also a beautiful new marble monument in the northeast corner of Lafayette cemetery bears silent testimony to those who died at Columbine. More Pictures From the Columbine Mine Massacre Memorial Service

Columbine Mine Massacre Marker Map

Support a Stamp for Coal Miners

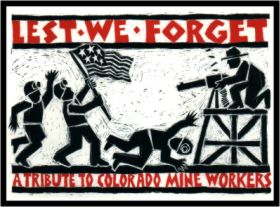

Lest We Forget artwork by Hal

Aqua |