|

Victor

|

The

Pinkerton Labor Spy

by

Morris Friedman

CHAPTER XX.

PINKERTONS AND COAL MINERS

IN COLORADO NO. 38, ROBERT M. SMITH.

Despite the fact that with the assistance of Operatives Strong and Smith, the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company prevented their coal miners from organizing, the latter, nevertheless, managed to maintain a halfhearted, inactive union in the State, known officially as District No. 15.

The brave struggle put up by the Western Federation apparently instilled a little courage into the faint hearts of the coal miners, for at the convention held by them in Pueblo, September, 1903, there seemed to be a unanimity of purpose to do something definite to improve the conditions under which for so many years they had been oppressed and ground down.

Deeply interested as they were in the affairs and plans of the United Mine Workers of America, the Fuel & Iron Company and the Pinkerton Agency felt they would be doing injustice to themselves if they did not participate in the deliberations of the convention. To accomplish their benevolent purpose, Operative Robert M. Smith attended the convention as a delegate from a Southern local, and assisted his brother delegates as best he could. True, the convention was open; yet a report of the proceedings by a Pinkerton operative was more desirable and reliable, in the opinion of the Agency and the coal company, than a similar report from newspaper representatives.

The following reports of Operative Smith will give the reader a fair idea of what the coal miners of Colorado, in convention assembled, spoke, did and planned:

Dear Sir:—

OPERATIVE NO. 38 REPORTS:

Pueblo, Colo., Thursday, Sept. 24th, 1903. The first thing that took place this morning was a lengthy discussion as to whether the press reporters should be allowed in the convention. Howells contended that the more publicity we gave our deliberations, the better, as it was the public mind we wanted to reach, and it was finally decided to let the reporters remain as long as they reported truthfully the actions of the convention, but that on the first false report going out, the reporter giving it, and the paper he was working for, would be excluded from the convention.

The President's report was then read, and dwelt principally upon the efforts that had been put forth within the last year toward the organization of District No. 15, and the almost utter failure of the efforts. It also dwelt at some length on the efforts of himself and others to get a meeting with the operators of District No. 15, to adjust an equitable wage scale, and its failure also, and he offered some recommendations as to his views with relation to precipitating a strike in District No. 15, which all present seemed to fully concur in.

The sentiments of all delegates present, except John Gehr and Jim Ritchie, are enthusiastically in favor of a strike, and they are anxious to see it declared as soon as we get a substantial promise from the National that we will be supported. Jim Ritchie offered a resolution to the convention, commending the striking miners at Cripple Creek and roundly condemning the Governor and Sherman Bell. The resolution was referred to the Resolution Committee. There was then a committee chosen consisting of Smith, of Erie, Colorado; P. P. Mort, of Colorado Springs; J. L. Campbell, of Fremont County; James Kennedy, National Organizer, and William Price, of Palisades, to draw up a wage scale to present to the operators for adoption, and if they refused to consider it, it would be placed before the National Executive Board for their approval; and if they approved it, a strike would be called immediately after the National Executive Board meeting, October 5th.

There was a telegram from an operator at Port Smith, Arkansas, to the effect that 500 union coal miners could get work at once in that vicinity. The dispatch was heartily applauded. The convention then adjourned at 5.30 P. M. until 9.00 A. M. to-morrow, and after supper myself, Jim Kennedy, Wm. Price, State Labor Commissioner Montgomery, Mr. Hamilton, organizer for the American Federation of Labor, and several other delegates, started out to take in the town.

Montgomery told me he was here as a personal representative of Governor Peabody, and he could say that we miners had the sympathy of the Governor, and that we had his (Montgomery's) full sympathy, and he would use his full influence to keep the Governor on our side, and he considered his influence with the Governor pretty strong. Hamilton substantiated his statements, and said he believed the coal miners were fully justified in their demands, and the Governor thought so too; but, of course, the delegates are a little skeptical in accepting such statements in view of the prevailing conditions at Cripple Creek, and also the fact that Montgomery was somewhat intoxicated when he made the statements. He said he was going to address the convention while here, defining his position, also that of the Governor toward the coal miners of Colorado.

We were out until after midnight, when we retired for the night

Friday, Sept. 25th, 1903.

This morning the Scale Committee offered the following scale for consideration and ratification of the convention:

Demand No. 1, an eight-hour day; No. 2, semi-monthly payday ; No. 3, abolition of the scrip system; No. 4, better ventilation in mines; No. 5, twenty per cent, advance on all contract mining; No. 6, that all company or day men receive the same pay for eight hours as is paid now for ten hours.

This caused a lengthy discussion, F. P. Mott, delegate from the Springs, taking the stand that the various unions in El Paso County had already presented their yearly agreement to the operators of that place for their ratification, and that they had until October 1st to sign up, and that this scale would abrogate the El Paso miners' contract, and would place them in the position of repudiating their own contract, but he was finally convinced that the 15th District was larger than El Paso County, and that legislation at a district convention took priority over any local or sub district contracts or legislation.

Then John Gehr took a stand in opposition to the scale, saying the operators would never agree to it, as it was asking entirely too much, and would surely cause a strike if we tried to enforce it. He was opposed by all the delegates, except Jim Ritchie, with the argunient that it was not too much to ask, and they did not care if it did cause a strike, as they practically had the assurance that the National Board would endorse it and support them in case of a strike. Gehr then said he as National Board member, and the proper one to place said demand before the National Board, would not carry such a demand before said board, as he did not consider it a fair demand, or entitled to the consideration of the National Board, and did not think we stood one chance in 100 in enforcing such a demand, even by striking, and he did not favor a strike anyway until we were more thoroughly organised.

The fact was pointed out to him by Kennedy and others that we could not continue the organization under the tyrannical methods employed by the operators at all the camps in the South, and that he was a servant of District No. 15, and would have to carry out the demands of District No. 15, or cease to work for District No. 15, but if he would not carry the demands of District No. 15 before the National, that Con Kelleher would. Kelleher had already signified his willingness to do so. Gehr was drunk all through the sessions of the convention, and he left the convention in a rage, and the demands were fully ratified and ordered printed, and a copy ordered sent to each of the coal companies operating in District No. 15. This took up the time until noon and was not finished until some time in the afternoon.

Then Con Kelleher gave the convention an address, reiterating the statements made to me several days ago, and which I reported at the time, that John Mitchell had instructed him to make the fact that he had met and conferred with John Mitchell as public as possible, and that Mitchell was going to convene the National Executive Board October 5th for no other purpose than to consider the grievances of District No. 15, and he had instructed him (Kelleher) to return to District No. 15, and have the convention draw up a scale, and come to the National Executive Board meeting and lay the scale of District No. 15 before that body, and John Mitchell had as good as told him he thought the fight of District No. 15 would be taken up by the National.

He also said he had talked with a number of the operators of Missouri while there, and all of them begged him to send all the men to them he could in case Colorado came on strike. This news was received with applause. This and minor matters consumed the balance of the day, and at 5.30 the convention adjourned until 9.00 o'clock to-morrow.

After supper I undertook to write up my report, but was interrupted several times, and when I finished yesterday's report, I gave it up, and went out with a number of the delegates and took in the town until about midnight, when we returned to the hotel, and I soon retired for the night. The sentiment of all the delegates with whom I discussed the subject was, that there never was a more opportune time than now to make such a demand as we were now making, and they all thought that with the support of the National we ought to win in a great measure, at least.

Saturday, Sept. 26th, 1903. This morning there was a resolution introduced condemning John L. Gehr for an article which appeared in the "Pueblo Chieftain" this morning, which is attached. This caused quite a wordy battle in the convention, as in the original resolution there was a paragraph to the effect that Gehr was continually intoxicated. Moran, Ritchie and Tom Hurley said that while that was the truth, it was putting it too strong to the public, and Jim Kennedy, Julian Gradel and a number of others said it was not strong enough, as he deserved greater censure for what he had done.

The resolution finally passed with the clause pertaining to his intoxication stricken out.

Gehr was not present, having gone home last night. This was one of the reasons given by Jim Ritchie for fighting the resolution. There were several resolutions of minor importance, also several minor amendments to the constitution submitted, and passed, which took up the time until the noon adjournment, and the first thing after reconvening in the afternoon, Chas. Moyer, President of the W. F. of M., was introduced, and spoke at some length on Trades Unionism, Socialism and the Cripple Creek strike and militarism, and in conclusion said he believed the W. F. of M. would eventually win their strike, and he hoped the U. M. W. of A. would immediately demand the eight-hour day, which, he believed, would strengthen the position of the W. F. of M., and he hoped the U. M. W. of A. would succeed in forcing the autocratic operators to comply with their demands, and that they had the sympathy of the W. F. of M., and any financial aid that the W. F. of M. could give them. John C. Sullivan, President of the State Federation of Labor, was then introduced, and talked at some length on the failure of the 14th General Assembly to pass the eighthour bill, and said he believed that the only eight-hour bill which would stand was the eight-hour bill passed by Organized Labor, by refusing to work longer.

He also went over the Cripple Creek situation, and predicted the ultimate success of the strikers, and said he hoped the U. M. W. of A. would get some concessions from the operators, but he was afraid it would take a strike to bring these same operators to their senses, and that the U. M. W. of A. had the entire sympathy and moral support and whatever financial aid the State Federation could give. At the conclusion of Sullivan's remarks, a resolution was introduced declaring for a free interchange of transfer cards with all legal unions, which after some discussion passed.

The resolution condemning the Governor was then taken up and unanimously passed. Then the grievance of the locked-out men at Rugby was taken up, and after some discussion there was a resolution passed that the district give Rugby $100.00 now, and that each delegate on his return home request his union to donate $5.00, and as much more as they can spare to re-imburse the district treasury, and that if more than $100.00 comes in from this call, the excess is to be given to the Rugby union.

The canvassing board then declared the following officers elected for the ensuing term: National Executive Board Member, James Kennedy; District President, Wm. Howells; District Vice-President, James Graham; District Secretary-Treasurer, John Simpson; District Executive Board Member for Sub District No. I, Chas. Billington, Louisville, Colorado. Sub District No. 3, I did not get.

Sub District No. 4, Robert Beveridge, Aguilar, Colorado. Sub District No. 6, Frank Hefferley, of Blossburg, and Mr. Harlem were nominated and referred to a referendum vote of the sub district for a choice, this being a newly-created sub district taken from Sub District No. 4. After deciding by vote to hold the next annual convention in Pueblo the third Monday in September, 1904, and having a few short talks from the newly-elected officers, the convention adjourned sine die, and after supper the entire crowd of delegates took in the town together until about 10.00 P. M., when they began leaving for their respective homes, and at 1.30 A. M. I took the train home, where I arrived at about 6.00 A. M.

Yours respectfully, ................

As the reader will observe in the above reports, it was the sense of the convention that unless they made a determined stand for their rights, their organization would soon fall into irretrievable ruin, a misfortune which would subject the coal miners indefinitely to the grind of a system destructive alike to body and soul. Therefore, in order to save the union and themselves, the miners laid their just grievances before John Mitchell, National President of the United Mine Workers of America, and begged him to come to their assistance.

President Mitchell responded to this appeal, and wired the management of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, asking for an interview between the operators and the union looking toward a peaceable adjustment of the miners' grievances. The company, in answer to Mr. Mitchell's request, sent him this telegram :

Denver, October 7th, 1903. John Mitchell, Indianapolis, Indiana.

Answering your telegram of yesterday in Mr. Hearn's absence, I have to say that we have not been advised and do not believe that our miners have any desire to strike, as we have always been able to adjust directly with them any differences that exist.

We do not think your organization is authorized to represent our miners, as very few of them belong to it.

If you understand the situation as it really is, you no doubt regard the inciting of any further industrial disturbances in Colorado as ill-advised and criminal.

J. F. WELBORN.

In this telegram Mr. Welborn gives one the idea that the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company was absolutely ignorant of the doings of the coal miners' union, and innocently believed that their employees really had no cause for complaint. Considering that they kept jealous, ceaseless watch on their men, openly through deputy sheriffs, secretly through Pinkerton operatives, it would seem to us that the above telegram is either a white or a black lie. Regardless of color, the fact remains that the telegram of the fuel company to President Mitchell is a lie, and an insolently-worded one at that. However, nowadays a corporation can behave as it pleases, when thousands of bayonets are at its command for the mere asking.

Besides, the company actually hungered for a battle. Its position was so secure, and its plans for defence and offence so perfect, that a conflict, particularly during Governor Peabody's administration, could only end with ignominious defeat for the coal miners, and would enable the company to give the latter such a lesson that they would not dare to think of striking again for years to come.

President Mitchell accepted the challenge implied in the company's telegram and ordered the coal miners of Colorado to strike. In brief, the demands of the miners were, an eight-hour day, increased wages, payment of wages in United States money, and the right of the men to join a union.

In the beginning the strike seemed destined to succeed. The demands of the poor miners were so just, that their cause ought to have won on its merits. Again, almost all the coal miners in the Southern fields had responded to the call, quit work, and affiliated with the union.

The United Mine Workers of America and the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company now faced each other on the industrial battle field, the former confident of success, the latter grimly secure in the knowledge of victory already won.

Operatives Smith and Strong, being old and tried union men, were now able to render good service. Operative Smith was at this time especially worth his weight in gold to the company, for he possessed the absolute confidence of the leaders of the strike, and knew days in advance what the union intended to do. Thus, if the leaders secretly planned to send an organizer to a certain camp to address, encourage and get together the men of that camp, Operative Smith would at once send the news to the Agency and the company.

As a result of Operative Smith's "clever and intelligent" work, a number of union organizers received severe beatings at the hands of unknown masked men, presumably in the employ of the company.

The following incident was one of many events of a like nature that helped break the coal miners' strike.

About February 13th, 1904, William Fairley, of Alabama, a member of the National Executive Board of the United Mine Workers of America and the personal representative of President Mitchell in the conduct of the Colorado strike, had addressed coal miners' meetings near the towns of Hastings and Majestic. Assisting Mr. Fairley was James Mooney, of Missouri, also a member of the National Executive Board of the union. The town of Hastings is an almost impregnable stronghold of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, a town which the unhallowed feet of a union organizer may not enter.

After the union leaders had left Majestic, and while they were about one and one-half miles from Bowen, eight masked men held them up with revolvers, dragged them from their wagon, threw them to the ground, beat them, kicked them, and almost knocked them into insensibility. More than likely Operative Smith subsequently listened to their tale of woe with indignantly flashing eyes, and bewailed the cruel fate which seemed to dog them at every step.

We cannot blame the coal miners' union for their failure. How should they know that their most dangerous, implacable enemy was one who for years had been and still was above suspicion, in fact, one whose apparent zeal and self-sacrifice endeared him to all his comrades?

On Saturday, April 30th, 1904, W. M. Wardjon, a national organizer of the United Mine Workers, while on board a train en route to Pueblo, was assaulted by three men at Sargents, about thirty miles West of Salida. Mr. Wardjon was beaten into unconsciousness.

The Colorado Fuel & Iron Company will naturally disavow their connection with these outrages; yet, we ask, and the public asks: How was it possible, in the first place, for anyone not on the inside of things to follow up the route of the union organizers so correctly? In the second place, can we believe that men will mask themselves and beat their fellow-men into insensibility, unless they are ordered to do so by someone above them, and paid well for their criminal services? Third, it is impossible to believe that the leaders of the union hired thugs to hold them up, and unmercifully beat them. Fourth, there was only one way whereby the moves of the union leaders could be accurately known in advance by any outsiders, namely, through a leak in the union. Fifth, we know that this leak was in the person of the talented Pinkerton Detective Robert M. Smith. Sixth, as the latter reported exclusively to the Agency and to the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, there can be no doubt on earth that the outrages described were committed by thugs hired expressly for that criminal work by some responsible official or officiate of the company.

People have been condemned to death on circumstantial evidence far weaker than is ours; and we can see no reason why, in the interests of a common brotherhood, such rascally methods as were very probably adopted by the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company with the active co-operation of Pinkerton's National Detective Agency, should not be thoroughly aired before the public.

Turn as they would, the leaders of the coal miners in Colorado met shameful defeat. Trained and veteran leaders of the United Mine Workers, who had achieved notable victories for President Mitchell in Eastern States, met their Waterloo in the Colorado strike. That wolf in sheep's clothing in their midst, that man who was a coal miner by trade and a Pinkerton operative by profession, circumvented all their plans, defeated all their hopes, and helped rivet the shackles of a miserable servitude more closely than ever before on the emaciated limbs of those men who trusted implicitly in his loyalty and honor, and called him "BROTHER."

After playing with the bewildered strikers for two or three months, much the same as a cat does with a mouse, the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company decided to end the already broken strike, by letting loose the military on the unfortunate miners.

We hate to refer again to Governor Peabody. The very mention of his name has a sickening effect. But again refer to him we must, and will.

Somehow the coal miners had got the foolish idea that Governor Peabody was very friendly to them, and would do all in his power to advance their cause with the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company. Never was a more grotesquely pitiable mistake made. . . . Justice and compassion from this tool of capital?

His Excellency never hesitated to tell a falsehood. The reader has noticed that. But we cannot give this one-time governor the credit for being even an expert liar. Governor Peabody was an amateur at the calling, and a bungler. The following incident demonstrates the truth of the statement, and also proves how friendly the governor was to the coal miners.

On August 21, 1903, a committee of the United Mine Workers of America, consisting of President William Howells of District No. 15; John L. Gehr, a member of the National Executive Board; and Duncan MacDonald, a National Organizer, came to Denver for the purpose of enlisting the governor's aid in behalf of the miners. The committee felt emboldened in approaching the governor because it was generally understood that Colorado's executive felt friendly toward the good coal miners, and really would not deal with them harshly as he had dealt with the bad Western Federation of Miners.

The committee went to the State Capitol, where they requested an interview with the governor. The governor's private secretary told them to call again in the afternoon at 2.30. When they called at the appointed time, they were informed that the governor would not receive them. One of the committee later said to a representative of the press: "He was perfectly willing to meet with us as individuals, but to treat with us as a committee, never."

On July 30th, 1904, after all the strikes had been suppressed by the militia, Governor Peabody published a statement in the press, from which we quote:

"It will be a matter of great regret to me if the laboring men of this State fail to see that I am fighting their battle, for I sincerely believe that Organized Labor has no more dangerous enemy than the Western Federation of Miners, which is seeking under the cloak of Organized Labor to protect itself alike in the promulgation of its dishonest Socialistic theories, which recognizes no right to private property, and from the result of its anarchistic tenets and tendencies. Legitimate labor organizations of necessity suffer from the criminal aggressions of the Federation."

Here it is: On August 21st, 1903, Governor Peabody would not even extend a committee of the conservative and legitimate United Mine Workers of America the courtesy of an interview, because they called on him as representatives of a labor union. Scarcely one year later, on July 30th, 1904, the same governor poses as a friend of labor, and would give the latter a bit of fatherly advice by warning "LEGITIMATE LABOR ORGANIZATIONS TO BEWARE OF THE CRIMINAL AGGRESSIONS OF THE WESTERN FEDERATION OF MINERS."

Had Governor Peabody been an artist, he would never have published the above statement.

And now let us see how the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, after having shattered the strength of the strikers and broken the courage of their leaders through the clever work of Operative Smith, finally tipped over the already tottering wall, and buried in its ruins the last atoms of resistance to their unscrupulous methods.

The betrayed union leaders were discouraged and weary of the strike within about three months after its commencement, and the rank and file shared in the despondency of their chiefs. The Colorado Fuel & Iron Company knew the state of mind of both leaders and men, thanks to Operative Smith. They decided that the time was now ripe to put the finishing touches to this miserable struggle by calling on the governor to send the militia down to Las Animas County to teach the miners that the modern definition of "STRIKE" is "REBELLION."

Governor Peabody, who would not treat with the representatives of a labor union in their official capacity, had no hesitancy in going down on his knees before capitalists who "demanded" that he send troops to wage war against men whose crime was that they wished to be treated like human beings and not worse than dogs.

We know we cannot surprise the reader by telling him that on March 22nd, 1904, the governor declared the County of Las Animas to be in a state of insurrection and rebellion. The surprise comes rather in the wording of His Excellency's proclamation, which is almost identical with his previous proclamations placing San Miguel and Teller Counties under martial law.

This last proclamation proves what an inconsistent and reckless falsifier Peabody was, and bars him forever from the society of artistic liars.

The governor, in his final message to the State legislature, had this to say under the heading of INDUSTRIAL TROUBLES:

"Early in my administration a certain organization known as the Western Federation of Miners, claiming public consideration under the name of Labor, whose officers and those in direct charge of its management are bold, careless, reckless men, attempted to ferment trouble in several of the industrial sections of Colorado to the end that that particular organization should have recognition in the operation and management of the mines, mills and smelters wherever located in the State, which effort culminated in the arbitrary calling of the most senseless, causeless, unjustifiable and inexcusable strikes ever known in this or any other country.

"Believing that my duty to the people of this State lay in protecting life and property in advance of annihilation, I proceeded to stop the unlawful methods of this reckless band of men. The incidents of the altogether too long conflict are so familiar to every resident of Colorado, I shall not dwell upon them. Suffice it to say law and order was maintained, peace restored and prosperity immediately followed.

"Anarchy cannot continue under our American form of government, and the people of this State breathe free in the knowledge that they are entitled to lawful protection, and when the laws are enforced, can obtain it."

According to his proclamation placing Las Animas County under martial law, the United Mine Workers of America, like the Western Federation of Miners, were a:

"Class of individuals which are fully armed and are acting together resisting the laws of the State, and that at different times said persons and individuals have committed various crimes, and that from time to time attempts have been made by said parties to destroy property," etc., etc.

Despite the fact that in the above proclamation he painted the coal miners as black as the coal they mined, the governor, in his message, never mentioned one word about his outrageous campaign against them, a campaign which for cruelty and brutality could not, we believe, be paralleled even in the annals of Ivan the Terrible.

Assuming that the governor said nothing about the coal miners' strike, because of the great wrongs he had done them; also considering that he proclaimed them as outlaws in the same manner that he had outlawed the quartz miners; knowing as we do, that whatever crimes were committed in the Southern coal fields, were on the persons and property of the strikers,—it follows that the governor's proclamation affecting the coal miners is as black a fabrication as the hearts of the officials of the coal company.

As the word of a notorious fabricator would not be believed under oath by a jury, we cannot see why Peabody's word should be believed when he charges other persons or organizations with the crimes that he charged the innocent, atrociously persecuted members of the United Mine Workers of America.

Major Zeph T. Hill was appointed commander of the militia in Las Animas County, with headquarters at Trinidad. Major Hill was a very energetic officer, and the coal miners, no doubt, remember him with great affection.

Curfew was established and enforced. No person was allowed on the streets after 9 o'clock in the evening.

The coal miners were photographed like notorious criminals, by the Bertillon system. Eighty strikers at Berwind, who objected to being thus humiliated, were marched by a detail of cavalry for twenty miles to Trinidad, in a scorching hot sun, where sufficient force was available to photograph and register these men according to the Bertillon system. The men were given nothing to eat or drink on the road, and one man who fell by the road-side was left lying in the sun. This event occurred on May 19th, 1904.

Meetings of the coal miners' union were forbidden, unless a soldier was present at every meeting.

The press, the telegraph and telephone were placed under rigid military censorship.

Coal miners were deported from the State by trainloads, without reason and without appeal.

The union had established a little colony of tents known as Camp Howells in "Packers Grove," located in the river bottoms near Trinidad. About 400 striking coal miners lived in this colony, where they were provided for by their national organization. The Colorado Fuel & Iron Company knew that these men, comfortably situated as they were, would never give up the strike, so they apparently gave secret instructions to Major Hill, who, on the pretext that the camp was unsanitary, gave the miners three days to clear out and disperse. The miners humbly obeyed this order.

This was a campaign against American citizens who wanted to work eight hours and to receive their wages in lawful money of the United States.

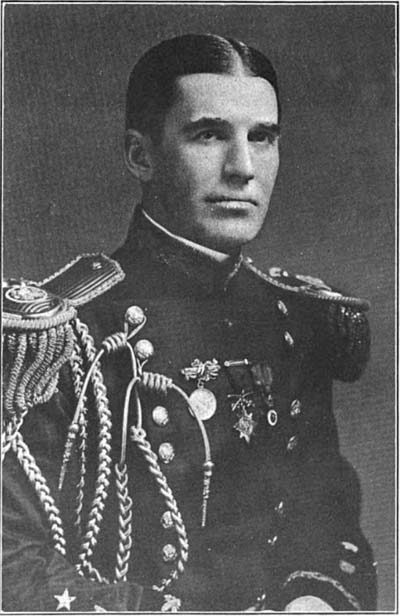

GEN. SHERMAN BELL

The coal miners could not stand the oppressive rule of the military. President Mitchell wisely concluded that so long as a sworn tool of the corporations was the governor of the State, labor could not hope to get fair treatment, and he therefore ordered the Colorado unions to call the strike off, and withdrew the support of the national organization from Colorado. The Colorado union officials stubbornly refused to obey President Mitchell's orders, and continued the strike a short time longer, when it fell of its own weight.

The strikers humbled themselves before the triumphant coal company and returned to the mines again to toil twelve-hour shifts, and again receive their hard-earned wages in the SCRIP which enables the company to sell to their employees the necessaries of life at atrociously high prices.

During the few months that the strike had lasted, the United Mine Workers of America had expended a huge sum of money.

When the strike was over, President Mitchell decided to appoint a reliable man to attempt again to organize the coal miners, despite the vigilance of the company. As a good salary was attached to this position, there were plenty of candidates; but, after thoroughly considering the various applicants, President Mitchell appointed as national organizer for the United Mine Workers of America, that tried and true devotee of unionism, that incorruptible foe of corporate tyranny and aggression, that virtuous, intrepid, rare and conscientious friend of labor, who had done so much to make the coal miners' strike a success, PINKERTON OPERATIVE ROBERT M. SMITH, NO. 38.

And the officials of Pinkerton's Agency, and the officials of the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, laughed as well as hard-hearted men are able when they heard how completely the leaders of the United Mine Workers had been duped; especially by No. 38, who of all others had done the most effective work to break the strike of the coal miners in Colorado.

Chapter XXI. Pinkerton and Coal Mines In Wyoming—No. 15, Thomas J. Williams.