|

Victor

|

THE CONFESSIONS AND AUTOBIOGRAPHY

OF

HARRY ORCHARD

CHAPTER TWELVE

HOW I WENT TO SAN FRANCISCO

AND BLEW UP FRED BRADLEY

WHEN I had been gone about six weeks from Denver after the Independence depot explosion, I went back there, and met Haywood and Pettibone at the latter's residence. I told them of my trip through Wyoming. I did not tell them I had lost my money gambling, but said that I had invested it in some real estate at Cody, Wyo., and that I needed some more money, because Johnnie Neville and I were going into the saloon business there. I got some money from Pettibone then. But we decided that it would not be safe for me to go back to Cody, as Haywood and Pettibone said there was no doubt about the authorities at Cripple Creek being after me.

They told me they had Art Baston working on Governor Peabody, but that he seemed to be slow, and Haywood told me that he was married, and that they did not seem to work so good after they were married. They told me about Andy Mayberry, superintendent of the Highland Boy mine at Bingham, Utah, discharging 150 union men because they laid off to take part in some labor demonstration, and Haywood said he wanted me to see Art Baston, and thought he would like to send us up there and put Mayberry out of the way, as he said they could not allow a man to do that kind of thing with the union men, or the union men there would think they had no protection from the union.

Pettibone made an appointment with Baston, and I met him at Pettibone's store one evening. He said he had been around Governor Peabody's place some, but that Adams had told him about us being there close to his carriage with the shot-guns, and the women seeing us, and Baston said he was a little leary about hanging around there, for fear Peabody had guards.

Right after that—some time in August, 1904—I met Haywood and Pettibone on a Sunday afternoon, and we had a long talk in Pettibone's back yard. They told me that Adams had gone up to Wardner, Idaho, to help Jack Simpkins get rid of some claim-jumpers that had jumped his and some other claims, and that after that Steve was going down to Caldwell, Idaho, and get ex-Governor Steunenberg of Idaho. They asked me if I knew where Gordon Post-Office was up there, as they wanted to send Jack some money there to give to Steve, to come down to Caldwell on when he got through with this job for Simpkins. I told them I did not know where Gordon Post-Office was, but if Jack told them to send it there, likely it was all right. But they said they would send it to Ed Boyce at Wallace, and he would give it to Jack.

STEVE ADAMS

Who confessed in writing to being Orchard's partner and co-worker in the field of professional murder. Adams subsequently repudiated his confession.

They also said Adams was going to stop at Granger, Wyo., on the way up to Idaho, and Haywood said that he had given Adams instructions to look up where the gang of train-robbers and bank-robbers and hold-ups called the Hole-in-the-Wall gang were. Haywood was going to get this gang to kidnap Charles MacNeill of Colorado Springs, manager of the United States Reduction and Refining Company, who was the chief man that fought the union in the Colorado City Mill and Smeltermen's union strike. Haywood said if he could get this gang in with him, and kidnap MacNeill and hold him for ransom, they would get as much money as the strike would cost them. This gang had headquarters in the Big Horn Mountains, where you could look out for miles over the level and see anybody coming. They said the only way you could get up where they were was through a very narrow box cañon, and they had that fixed so that a regiment of soldiers couldn't get through there without being killed off.

But the man they sent Adams to told him there was none of the gang there then; that they were all South; Adams wrote Pettibone a letter, and said "the birds had all flown South."

We talked over our going to Bingham, Utah, and I told Haywood I was well acquainted there, and was also acquainted with Andy Mayberry. He said if I was I had better not go there. He said they had some work in California, and thought I had better go down there, and he said they had some of this old work that they had wanted done a long time, and that this was the best time he knew of, as they had plenty of money, and could get it out easier now and it would not be noticed so much. They received more money the next month after the convention than any month during the trouble; I think they received between $40,000 and $50,000 for the strike or eight-hour fund, as it was called.

We held this latter conversation one Sunday in Pettibone's back yard—Haywood, he, and I—and Haywood finally asked me if I would go to California alone and see if I could put Fred Bradley out of the way. Mr. Bradley was manager of the Bunker Hill and Sullivan mine at the time of the trouble in the Cœur d'Alenes, Idaho, in 1899, when they blew up their mill, and Haywood said he was at the head of the mine operators' association of California, and he said they were raising an immense fund to drive the Federation out of the State, or words to that effect. He said they wanted to show those fellows that they never forgot them. He also said he had sent Steve Adams and Ed Minster to California to get Bradley, but they did not accomplish it. I told them I would go down and try it.

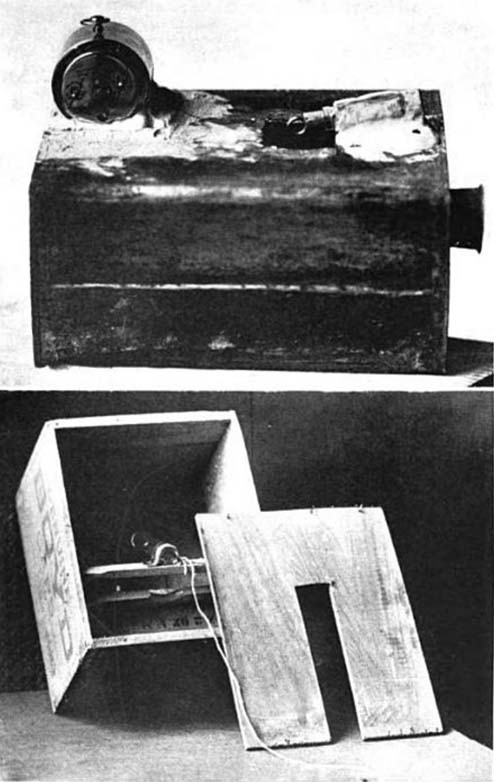

THE TWO STEUNENBERG BOMBS

From models made by Orchard. The lower of these failed to explode. The ex-Governor was killed by the upper one; the clock on this was not used, the cork of the bottle of acid being pulled out by a string fastened to a gate.

The next day, I think, Haywood gave Pettibone $150 more, and he got me a ticket and a new grip, and I took the early train the next morning for San Francisco. Pettibone told me any time I wanted any money just to wire him and he would send it to me. I went by the name of John Dempsey. I arrived in San Francisco in a few days, and stopped at the Golden West Hotel. I looked around in the city directory and the telephone guide, and located Mr. Bradley's office and also his residence, and called up his office by phone, and they told me Mr. Bradley had gone on a trip to Alaska and would not be back for three months. I wrote a letter to Pettibone and told him this. We had a sort of a cipher to write by, so no one could tell anything about it if it fell into their hands. I also told him in this letter to send me $100.

During the time I was waiting for an answer I noticed in the paper where Johnnie Neville had been arrested at Thermopolis and was being taken back to Cripple Creek, and that they also expected to arrest me soon and take me back there, too; so I thought I had better leave the hotel and get a private room, and not go around much in the daytime. But I had told Pettibone to address me at the Golden West Hotel, and had not received his letter yet, but had gotten a telegram from him stating, "Business bad, Johnnie on the way, wrote you to-day." I did not want to stay at the hotel any longer, but I wanted to get this letter, so I went and hunted the secretary of the bartenders' union, named Peter L. Hoff, and arranged with him to get the letter for me at the hotel. I told him I was a union miner from Colorado. I left the hotel then and got a private room a little way out. Hoff sent a man down to inquire for the letter, and he said as soon as he asked the clerk at the hotel if there was any mail for Dempsey he touched a button. He thought he did this to call an officer, and he said the mail-carrier also happened to be there, and he spoke up and asked where Dempsey was, and he became more suspicious then, and said I was a traveling man and had gone to Stockton, Cal. The mail-carrier asked him my address, and he told him Stockton, Cal., general delivery. There was nothing in these manoeuvers—they just happened that way— but this man thought it looked suspicious, and so it did. I would say that when you are on work of this kind you soon become suspicious of everybody and everything, and, in a word, of your own shadow.

So Hoff wrote to Stockton, and told them to forward the letter to him at 211 Taylor Street, San Francisco, and he got a card in a day or so from the post-office on Mission Street, and there was a registered letter there for John Dempsey. I gave him an order to get it, but they would not let him have it. I did not want to trouble him any more, and he said he did not believe there was any one watching for me there, and that if I went down there he would identify me, so I went down with him later and got the letter without any trouble.

Pettibone told me to lay pretty low and not let them pick me up the first thing, and be careful, if I wrote to him, what I wrote, and to destroy his letters immediately. He also told me to go a little slow on money, as it was hard to dig up. I got the hundred dollars I sent for in this letter. I got the Denver papers there all the time, and knew pretty well what was going on in Colorado, and kept pretty quiet for a while, staying in most of the time during the day. But I got tired of this, and thought I would go out to some little summer resort and stay there a while, and I went up to Caliente Springs and stayed there about a month. I then came back to the city and got a room out near the Presidio. I noticed by the papers that they held Johnnie Neville in jail, and would not give him bail, and I noticed the names of several others I knew who were arrested. I used to send for $100 to Pettibone about once a month, and he wired it to me. He used to send this to Harry Green, in care of Peter L. Hoff. He sent this as coming from Pat Bone, or Bowen, and sometimes as from Wolff. I had some little trouble getting the first draft, as I was not sure what name he gave when he sent it, but I got it all right. Mr. Hoff was acquainted with them down at the postal telegraph office, and after the first time he identified me they used to give it to me without any fuss.

They held Johnnie Neville between two and three months, and then released him on his own recognizance, and also released all the others, only placing charges against two, and releasing these on bail. I felt more easy then and went around more, and Johnnie and his boy went back to Thermopolis and got the team and wagon, and drove back to Denver. I noticed these things in the papers.

I had bought ten pounds of dynamite to make a bomb with, and got a room only a few doors from Mr. Bradley's flat. This room was on Washington Street about a quarter of a block away, but on higher ground, and my windows were about on a level with the Bradley flat, and I could look right over into it. There was a little grocery store and a saloon on the opposite corner from Mr. Bradley's residence, and they used to buy their groceries there, or part of them. I used to loaf there in the saloon a good deal, and spent quite a bit of money with this man. He was an Italian or a Swiss. The girls that worked for Mr. Bradley used to be over at the store every day, and Guibinni, the proprietor, gave me an introduction to them. So I got to talk to them, and took one of them to the theater once, and found out from them when they expected Mr. Bradley home, etc. I stayed there until he did come home. I went by the name of Berry there.

After Mr. Bradley came home, some time in October, I noticed his movements, and learned his habits pretty well. He used to leave his residence about eight o'clock in the morning. They lived on the corner of Leavenworth and Washington streets, in a big three-story residence flat that had six families living in it. There was a big archway at the entrance, and the flat was built out flush with the sidewalk. They all went in at this archway, but each family had a private entrance to their apartment. I had figured a good many ways how to get away with Mr. Bradley the easiest and not get caught. I had stood across the street in front of the entrance to his residence, with a shot-gun loaded with buck-shot, and tried to catch him coming home at night; but it was not light enough to tell him from the rest, as they all went into this archway. I was getting sick of staying there, and Pettibone had sent an answer to my last letter, asking him to send me $500, to call it off, and did not send the money.

My money was getting low, and I was getting desperate, for I thought they just took advantage of me, not sending me money because they thought I dared not come back to Denver, and I made up my mind to go back and show them. I knew Haywood, Moyer, or Pettibone dare not refuse me money if I asked them personally.

The desperate and horrible means I conceived at this time to carry out my plan to kill Mr. Bradley I would gladly withhold and let die in my breast. But I feel that perhaps I owe some one a duty that may have been blamed for this, and wrongfully accused; and I feel it my duty to make this known, as I have promised God I will write the whole truth of my wicked and sinful life, and not try to favor myself. I have made this attempt several times, and it has required no small effort on my part to write some of these things.

I knew this place well, and there was an empty house with a flat roof just behind the apartment where Mr. Bradley lived, and there were stairs up from the back way on the outside of the apartment. I went up these stairs and got on the roof of this vacant house—for it was right close to the stairs—and waited there until the milkman brought the Bradleys' milk, which was a little before daylight. I knew he left this milk there in bottles, as I had watched him before. I had a little powder of strychnine made for each bottle, and raised the paper cover and emptied one of these in each bottle of the milk and cream, and stirred it up a little, and pressed the paper cover back again, and left and went back to my room. I figured the girls would serve Mr. and Mrs. Bradley's breakfast first, and they would get the poison first. I could see their kitchen plainly from the window of my room, but I could not see anything unusual there that morning.

I did not get up until ten and sometimes later, and then I usually went down to the little saloon bar at Guibinni's and got a drink, and sat there and read the morning paper. This morning I did the same, and I noticed a bottle of milk standing on the back bar, and asked Guibinni if he was selling milk, or drew his attention to the bottle in some way like that. He began to tell me about this milk, and wanted me to taste of it. He said he tasted of it, and could feel it in his throat yet. He told me the girls over at Mr. Bradley's had brought that bottle over, and wanted him to take it down and have it analyzed, as they believed there was poison in it. He said it was bitter as gall. Now I never knew before that strychnine was bitter, but it seems the cook had tasted of some of this, found it was bitter, and told Mrs. Bradley, and then they came over to Guibinni's place to get some more milk and cream for breakfast.

After this failed, I got a bomb ready. I bought a piece of five-inch lead pipe about a foot long at a plumber's, and put wooden ends in it. Then I hammered one side of it flat, so it would lie straight without turning over, and I cut a piece out of the other side, and turned back the flap, and fastened a little vial on this, so that when you filled it with sulphuric acid, and you pulled out the cork, the acid would run out into the hole in the pipe. Then I filled up the lead pipe with about five or six pounds of No. 1 gelatin, and put some caps and sugar and potash on top of this and opposite the hole in the lead pipe, so the acid would fall on them. Then I planned to hitch a little string to the cork of the bottle, and fasten the other end of the string in a screw-eye in a door, so when you opened the door it would pull out the cork and set off the bomb.

I practised with this while I was making it in my room, so as to see if the cork would come out of the bottle instead of moving the bomb. I had the dynamite in, but not the caps or acid, and I tried it by fastening a screw-eye and string on my closet door, and it worked all right. But one day I left the screweye and the string and the cork on my door, and went down-town, and forgot about it; and when I got home I thought that was a nice trick to leave that thing there, for I thought the woman that kept the house must have seen it when she cleaned up my room. But she never gave any sign she noticed it.

After that I watched what time Mr. Bradley usually came down-stairs in the morning, and how soon after he ate his breakfast. As I was on a level, or about so, with their dining-room in my room, I could look out of the window and see them when they were at their meals. I noticed Mr. Bradley came down-stairs soon after he had finished breakfast, and I had to guess that he would be the first one down-stairs, so as not to catch any one else. In order to be sure he would be at home, I called him up one night on a phone at his residence, and told him I was from Goldfield, Nev., and had some good mining property up there, and wanted to raise some money, or get some one with money interested, so I could develop it; and that I had been recommended to him, and would like to make an appointment to meet him. He said he would be pleased to meet me and talk the matter over at least, and could meet me the next morning at his office. I asked him if he could as well make it the morning after that, and he said he could—at nine o'clock, I think—and I told him all right. I did not want to try the bomb the next morning, as I was not ready.

The next night I went and fastened a little screw-eye in the door of his residence, where it opened out of the stairway into the archway, and the morning after I watched him from my room when he went into breakfast, and waited until I thought he was about half through. Then I took the bomb that I had all ready, walked up to his door in the archway, laid it down, and hooked a little cord over the screw-eye I had screwed in the door, and laid the mat over the bomb. This looked like a small parcel, as I had it done up in a paper.

I had told the lady where I was rooming, the night before, that I was going away for a while, and I had also taken my grip down-town the night before and left it at a saloon. After I left this bomb, I took a car and went down-town, and got another room down on Taylor Street. After I rented this, I thought I would lie down and sleep a while, as I had not slept much during the night. A little while afterward I was awakened by some one rapping at my door, and, on asking what they wanted, was told to open the door and I would see. I told them they had better get away from there, and a little while after they came back. I asked them who they were and what they wanted, and was told it was the sheriff and to open the door. I told them to wait until I dressed. I thought I had been seen putting the bomb at Mr. Bradley's door and had been followed. I dressed and took my gun in my hand and opened the door, intending to shoot if they wanted to arrest me. But the landlady was there when I opened the door, and explained to me that the sheriff had seized her furniture and was removing it. This was such a happy surprise to me that I left the house, and never said a word about the room-rent I had paid her, nor the annoyance they caused me. This always seemed a little peculiar to me, that I should happen in a place of this kind at such a time.

I think it was about four o'clock in the afternoon when I left there. I bought the Evening Bulletin to see if there was any account of anything about the bomb, and there was not a thing. I felt pretty uneasy, as I knew if it had not been exploded it would be sure to be discovered, and I thought I might have been seen there, and leaving that neighborhood that same morning I would be apt to be suspected. I thought, too, that when they found the way that bomb was set, the lady where I boarded would be sure to remember the screw-eye and string that I had left fastened to my closet door.

I took a walk over on the west side, a little out of the busy part of the city. I did not have money enough to leave the city, and felt pretty miserable, and the world looked more desolate to me than it ever had before. I could not see much for me to live for, and I thought everything was working against me. I could not settle my mind on anything or do anything. I was strong and able to work, but could not set myself about it, as my mind was in such a state, and I came nearer ending all then than I ever had before.

I went into a restaurant to get something to eat, as I had not eaten anything all that day. I picked up another evening newspaper, the Evening Post, and there was the picture of the explosion and a full account of it. This paper stated that Mr. Bradley would probably die, or at least lose his hearing and eyesight. They gave as the cause of the explosion leaking gaspipes and fixtures, and said the gas had escaped and filled the hall and the stairway entrance to Mr. Bradley's apartment, and as he lit his cigar coming down the stairway the gas exploded. When Mr. Bradley opened the door, practically the whole stairway and entrance into the archway was blown out, and Mr. Bradley was thrown out onto the sidewalk with the debris, and the flat was more or less shattered from one end to the other, and the glass was broken across the street and for some distance away. It seems now to me a horrible thing to say, but I felt better after reading this, for I knew I could now get a good piece of money without any trouble, as Haywood and Pettibone would be so well pleased.

I sent Pettibone a copy of this paper and told him to wire me some money at once, and he did so in a few days. After about a week I went up and looked at Mr. Bradley's place, and saw Mr. Guibinni, the grocer and saloon-man. He told me they thought Mr. Bradley would lose his eyesight. He said he did not believe that gas caused the explosion, himself—he thought it was a bomb; but he said Mrs. Bradley would not hear to such a thing, and said she had smelled gas escaping for some time. The owners of the property sued the gas company, and were awarded $10,000 damages, and when this was carried to the Supreme Court, they affirmed the lower court.

I stayed in San Francisco two or three weeks after the explosion, and thought I would take a trip back to Denver. I went and got a suit of soldier's uniform, and wore that to Denver as a disguise. I set off the bomb at Mr. Bradley's house November 17th, and I got back to Denver about the first part of December, 1904. I went to a rooming-house, and got a room a little way from Pettibone's store, and then telephoned him to come over, and a few minutes after he and Steve Adams came. We talked a little while there, and I told them if Mr. Bradley did not die, he was at least maimed for life, and would be deaf and blind. Pettibone was well pleased with this news, but said it was hard luck that it did not kill him. Really, Mr. Bradley got well after a while, and is neither deaf nor blind; but I thought then he was very badly hurt.

Adams had come back in September, and he and his wife were keeping house in Denver then, and Steve asked me to go home with him. I went with him, and Billy Aikman was stopping with them, and Billy Easterly had been there some. I asked Pettibone why he did not send me the money when I asked for it, and what he meant by saying to call it off. He then told me the time they had had with Johnnie Neville after he had been released from jail in Cripple Creek. He came to Denver and told them he knew all about their work, and especially the Independence depot, and that I had told him they hired me to do it, and if they did not give him $1,200 he was going to expose them. Pettibone said for a while he had them all up a tree, and they had it all planned to kill him if he kept on. He said that Moyer was especially excited over it. But finally they scared Neville off by springing on him how he set fire to his saloon, and saying they would tell the police, and then he quit and left the country and went to Goldfield, Nev.

NEXT: Our First Bomb For Governor Peabody, And Other Bombs For Street Work