|

Victor

|

THE CONFESSIONS AND AUTOBIOGRAPHY

OF

HARRY ORCHARD

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

MY EXPERIENCE IN JAIL AND PENITENTIARY

IWAS arrested and taken to jail at Caldwell the evening of the 1st day of January, 1906. I had never before been arrested. I now began to think over my past life and what it had brought me to, and, oh, how I regretted that I had allowed myself to be arrested, and had not sold my life as dearly as I could have done, and ended all, as I felt the life I had lived for the past few years was not worth living and that I would rather be dead than alive, and felt there was nothing left for me worth living for, and why suffer the humiliation in prison. I knew it meant a long siege at best, and I knew if I succeeded in clearing myself of this, that I probably would have to go to Colorado and face other charges there.

I thought of ending all, and that when my dear mother taught me many long years before about God and the future life came up to me, and I could not get these thoughts out of my mind, although I had denied them for years and tried to forget them and said many times that the hereafter did not trouble me, and that I did not believe in any hereafter, but that the grave ended all. But now when this stared me in the face, and the thought came of taking my own life, and taking the desperate leap into the great beyond, from whence there is no return, I knew then that down deep in my heart I did believe there was a God and a hereafter, and that I had only been trying to deceive myself all these years, because it answered my wicked purpose better. Now, although I had read the Bible some when I was young, I had never read it with enough interest to understand it, and remembered very little of it, but I thought it said that no murderer could enter the kingdom of heaven, or would not be forgiven. This troubled me, for I felt great remorse of conscience and felt repentant. I tried to keep up the bravado spirit, and appear unconcerned and deny the charges against me, but still I thought, if acquitted, the old life was not worth living, and I wanted to be sure whether there was hope for me, or forgiveness, or if I had committed the unpardonable sin. If I had been fully convinced of this and that there was no forgiveness for me, then I would never have undergone any torture or imprisonment, as I would have had nothing to live for.

Haywood and Pettibone had always told me if I ever got arrested not to wire or write to them, but that they would see that I had an attorney to defend me as soon as it was possible, and when Simpkins left me he had said, if I got into trouble and had to have an attorney, he would send Miller or Robinson, of Spokane. A day or two after I was arrested I got a telegram from Spokane stating that Attorney Fred Miller would leave next morning for Caldwell to represent me. This telegram was not signed, but I understood it. I waited for three or four days and heard no word of him, but in the mean time James J. Sullivan, an attorney that I knew from Denver and a personal friend of Pettibone's, came to see me, but they would not let me talk to him alone. He said he was going to Baker City on some business, and stopped off to see if it was me they had arrested. I felt sure they had sent him to me from headquarters. I told him I had thought of wiring him, and asked him if I could engage him to defend me, but he shook his head, and said it was a long way from home, and that he would advise me to employ a local attorney, and said if I wished he would look around and get me one. I told him I had expected Mr. Miller from Spokane, and had had a telegram from Spokane a few days before stating that he would leave the next morning for Caldwell, but had heard nothing more from him, and Sullivan said he would wire him and see if he was coming.

HARRY ORCHARD

From a photograph taken in January, 1906, shortly after his arrest for the murder of ex-Governor Steunenberg.

He sent Mr. Miller the telegram, and he answered he would leave for Caldwell on the next train, and he arrived there the next day or so. They let Mr. Miller see me alone, and he told me that Jack Simpkins had sent him, and that he had started when I got the first telegram. I think he said he got as far as Walla Walla, and they called him back, as the papers came out with big head-lines charging the Western Federation of Miners with the assassination of ex-Governor Steunenberg, and they did not want it to appear that any one had been sent by them to defend me, but thought they would wait until I wired them, because we must make it appear that I was putting up my own defense, and keep the Federation out of it. He also said that Robinson had told him before he left that they might make it appear that they were engaged by me to sue Dan Cordonia to recover the interest I had sold him in the Hercules mine or a part of it, so as to have it look as if they were my regular attorneys. I spoke about them being engaged by me before to collect damages from the railroad company for holding my trunk, but he said that was too small a matter.

I did not know Mr. Miller very well, having only met him once, and I told him I was going to put up my own defense, and had upward of $2,000, and had friends that would see me through, if this was not sufficient. He asked me if I did not have some mining property, or some friends I could refer him to that he could make it appear were putting up money for my defense. I told him I would give him an order to get the money all right. He said Jack had only given him $100, and asked me if I did not have any money there. I told Miller I had only a few dollars there and he said to never mind, he would get some money from home. I gave him an order, and told him to see J. J. Sullivan and have him send the money when he got to Denver. I told him Sullivan knew Pettibone and would get the money all right. I also gave him an order, or told him to see Lewis Cutler, of Salt Lake City, and he would turn him over a sixth interest in some mining claims he had at Goldfield, Nev. I had loaned Mr. Cutler a little money at different times, and he made this proposition himself the last time I saw him in Salt Lake City. Mr. Miller stayed until after my preliminary hearing, and I was bound over to the district court without bail. Mr. Miller then left for Spokane, and said he would be back in a few days, and stay there and work on the case.

Mr. Swain, of the Thiel detective agency, from Spokane, came to the sheriff's office at Caldwell, and they took me out in the office, and he asked me some questions, and I answered some of them. I told him I had been in the Cœur d'Alenes, and had been out hunting with Jack Simpkins just before I came down here. He asked me if I knew Haywood and Moyer, and I told him I had seen them and was slightly acquainted with them. I think I also told him that my name was not Hogan, but Orchard, and that I had a good reason for going under an assumed name, and would give the reason at the proper time. I knew I need not answer any questions, but I thought these things could be easily proved, and that it would look better for me to answer them. Later he wanted to question me further, but I told him I had told him all I had to say, and he did not trouble me any more.

I was in Caldwell jail eighteen days and they removed me to the State penitentiary at Boise. Mr. Miller wrote me two or three letters and stated he was waiting for some mail, and would be down as soon as it arrived. I think I had been at the penitentiary about ten days or two weeks, and the warden took me out into the secretary's office and introduced me to an old man—I have forgotten the name he used. He then went out and left us alone. I do not remember the first part of our conversation, but he said he had seen a paper with my picture in and got permission to come up and have a talk with me. I asked him who he was and what he wanted to talk to me for. He told me he was a detective, and went on and said perhaps if he had kept the same kind of company I had, that perhaps he would have found himself in the same position I myself was in, but he said he had chosen the right course. He said he would like to give me some good advice if I would take it. I told him I did not object talking to him, but I did not need any of his advice, and protested my innocence, and said I was being wrongfully persecuted. He said if I was innocent I was the victim of very unfortunate circumstances, and that he thought I had left a bad trail behind me, and he further said it looked bad for me going in and out of Denver so much and visiting Federation headquarters. He further said he did not believe I did this of my own accord, and that he believed I was in a position to be of great benefit to the State. I told him I knew nothing about the assassination of Mr. Steunenberg whatever, and that I did not know what he was trying to get at.

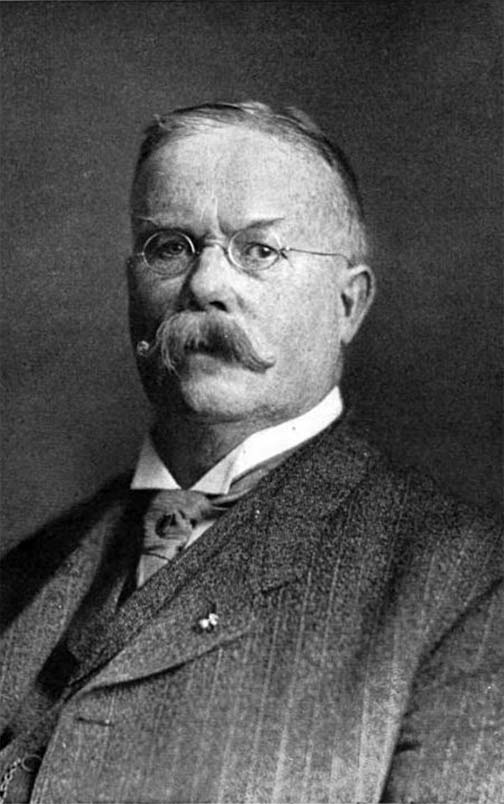

He asked me if I had heard of the Mollie Maguires. I told him I had heard of them, but did not know much of their history. He started to tell me about them, and it struck me right away that he was McParland, as Haywood had given me a description of him some time before. I asked him if his name was not McParland, and he said it was. He then went on and told me a lot of the history of the Mollie Maguires, and some of the parts he had played. I listened to him and said nothing much. I think at first he asked me about my people and if I believed in a hereafter and a God. I think I told him I believed in a supreme being or something like that. He also told me he believed I had been used as a tool. I think that was about the substance of what he said to me the first time he came up, and he asked me to think these things over when I went back to my cell. I protested my innocence all through, and told him I had nothing to think over. He told me I would be convicted of that crime, and that I would think of the words he had told me afterward. I told him I had no fear of being convicted. When he left he said that perhaps he would come up and see me again. I told him that it helped to pass away the time, and was a little more comfortable, or was a change.

DETECTIVE JAMES MCPARLAND

I think it was two or three days when he came back again, and I think he started in on my belief in the hereafter, and spoke of what an awful thing it was to live and die a sinful life, and that every man ought to repent of his sins, and that there was no sin that God would not forgive. He spoke of King David being a murderer, and also the Apostle Paul. This interested me very much, but I did not let on to him. I think I asked him a little about this, and he told me about King David falling in love with Uriah's wife, and ordering Joab, the general of his army, to put Uriah in the thick of the battle, and then ordering the rest to retreat, so he would be killed; and of St. Paul, who was then called Saul, consenting to the death of Stephen, and holding the young men's coats while they stoned him to death. I wanted to ask more about these things, but did not want to let on that they interested me. He also told me of some cases where men had turned State's evidence, and that when the State had used them for a witness, they did not or could not prosecute them. He said, further, that men might be thousands of miles from where a murder took place and be guilty of the murder, and be charged with conspiracy, and that the man that committed the murder was not as guilty as the conspirators, and, to say in a word, he led me to believe that there was a chance for me, even if I were guilty of the assassination of Mr. Steunenberg, if I would tell the truth, and he also urged me to think of the hereafter and the awful consequences of a man dying in his sins. He further said he was satisfied I had only been used as a tool, and he was sure the Western Federation of Miners were behind this, and that they were about to their limit, and had carried their work on with a high hand, but that their foundation had begun to crumble, as all such must that followed a policy that they had. He said further that they had had a gang of murderers at their head ever since their organization. He told me plainly he could not make me any promises, and if he did he could not fulfil them, but he said he would have the prosecuting attorney come up and have a talk with me. I told him that he need not trouble, I had not told him anything nor had I promised to at this time, but I told him to come up again the next day and I would let him know if I had anything to tell him.

I went back to my cell that night and tried to pray, and thought I would do almost anything if God would forgive my sins. But my past life would come up before me like a mountain, and I feared there was no chance for me. I thought, though the authorities in Idaho would let me go clear if I gave evidence and told the real men responsible for the murder of Mr. Steunenberg, that there were so many other crimes that I was guilty of that there would never be any chance for me. The only real hope I could see for me was to make a clean breast of all, and ask God to forgive me, but I felt very uncertain about this and prayed to God in a half-hearted way, and I felt a little hope at times, and then I would doubt, and think of self. I knew well the methods of detectives, and did not believe many things Mr. McParland told me; but my mind was in such a state, as I have before told you, I cared little what did become of me, and did not want to live any longer the old life, and when I would think of doing away with myself, the awful hereafter would stare me in the face, and something seemed to say to me that there was still hope. But I could not bear the thought of being locked up and every hour seemed like a month to me.

Now I had thought before I ever saw Mr. McParland of making a clean breast of all, but I would rather have him get the evidence than any one I knew, for the reason I knew his reputation, and knew there would be nothing left undone to run down everything I gave him. Then there came a doubt in my mind that this might not be Mr. McParland. I told him this when he came up the next day, and as he wore an Elk charm and I knew the Elks always carried a card that they used to make themselves known to a brother Elk, I asked him if he would mind letting me look at his Elk's card to satisfy myself that he was Mr. McParland, and he handed me his card, as he said no Elk was ashamed to show his card. After I was satisfied of this, I told him I was going to tell him all, and that he need not send the prosecuting attorney up; that I would not ask any pledges, but would tell the truth, and felt I did not deserve any consideration, and cared very little what became of me.

I told him I would tell him my life's history, and we talked over a part of my career that day, but nothing in connection with this case, and the next day Mr. McParland came up, and the clerk in the penitentiary took down my statement. I began at the first of my early life, and finished with the assassination of Mr. Steunenberg, but I kept a few things back that I thought too horrible to tell. We were three days at this. There were some things that no one in this country knew anything of, but I told them and in a way felt somewhat relieved. I felt that I had taken the right step, but when I thought of the awful ordeal I would have to go through to carry this out, and that I must face these men and give evidence that perhaps would send us all to the gallows, it seemed terrible to me. Sometimes I would think perhaps they would only send me to the penitentiary for life, and this I thought would be worse than being hanged, and that I would prefer the latter. I tried to pray and ask forgiveness, but this only in a half-hearted way. Sometimes I felt a little relieved, but other times I doubted, and I was very much in doubt whether God would forgive such a sinner, and I thought I would have to go through some long lamentation, and the greater the sinner the greater the sacrifice would have to be on my part. I wanted a Bible, but would not ask for it, and I did not want it known that I wanted to repent of my sins. I longed to read the Bible, but did not want any one to see me doing so, and every day seemed almost like a year.

During this time, or about the 20th of February, 1906, they brought Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone to the penitentiary and a day or so later they brought Steve Adams. I had told them about Adams being mixed up in other things besides what he was mixed up with me. The warden asked me before he brought Adams in if I thought best to put him in my cell, and for me to have a talk with him and persuade him to tell the truth. I told him I would do the best I could, and that I would tell him that I had told everything, but not at first, until I found out how he felt about it.

When Adams first came into the cell he did not let on that he knew me, or while the warden or guards were there, but after they left he began to talk to me and he spoke about my having made a confession. I laughed it off and partly denied it, but said I thought of doing so, and told him I thought it would be better for us to tell the truth and clear everything up and be done with it, as it was bound to come out some time, as so many knew about the crimes that we had been mixed up in, and that somebody was bound to tell of them some time—if not while they were up and around, some one would make a death-bed confession; and I told him I was tired of such a life and wanted to reform and ask God's forgiveness.

He said at first that he could not think of such a thing and spoke of the disgrace it would bring upon his people, and that there would be no chance for us at all, and he wanted me to go on through the trials and then we would tell those fellows to cut that kind of work out. I wanted him to lead a better life, and told him I could not rest, and that my conscience troubled me so that I did not want to live unless I could repent and be forgiven, and that I did not feel as though I could repent of my wrong-doing unless I told all, and made all the earthly restitution that was within my power to society, and clear my own conscience. He thought I would not feel any better after I had confessed all. I also told him there might be a chance for us to save our lives, as we had only been used as tools.

I talked to him, I think, two days on about the same lines, and he did not change his mind much, if any, and finally I told him that I had made a statement and told about all, and he asked me if I had told them about him. At first I told him that I had not, and he asked me to promise him that I would not, and I think at first I told him I would, but I finally told him that I had made a clean breast of everything, and told them all about the things he had been implicated in and wanted him to tell the truth. He said at first he did not see how he could go that kind of a route, and asked me if they had promised me anything. I told him I did not ask them to, but I told him the party that I had made my confession to had cited similar cases, and that those that had been used as tools, as we had been, had not been prosecuted. I also told him that I did not know if this were true or not. After I had told him all, I said to him to do as he pleased, but that I had told the truth and was going to stand by it, let the consequences be what they would to myself or any one else.

I told him the warden wanted to have a talk with him, and to go out and have a talk with him, and a few minutes afterward the warden came in and asked him to go out in the office, and he did. When he came back in he said the warden was a pretty good talker. I think that same afternoon Mr. Moore, Adams's attorney from Baker City, Ore., came up to see him. He did not tell me what he said to him, but a friend and neighbor of his named Bond, from Haines, came with Mr. Moore, and Steve told me that Bond had advised him, if he knew anything or had been used as a tool to commit any crimes, to tell the truth—or that would be his advice to him. Adams told me after that Moore had told him the State hardly ever prosecuted any one they used as a witness, and he said he thought he would do as I had done and tell the truth. He said that Moore had gone to Colorado to see the governor and find out if they would take Steve back there if he became a witness in this trial.

Mr. McParland came here the next afternoon and I had a talk with him and told him I thought Adams would make a confession, but perhaps not until after Moore had come back from Colorado; so Adams went out in the office and had a talk with Mr. McParland, and he told him he would make a confession and tell the truth in everything, and the next day Mr. McParland and his private secretary came up and took down his confession. I do not think there were any threats or promises of any kind used. Adams never told me if there were.

I was taken sick a little after this and they moved me over in the hospital, and a day or two later they moved Adams over there, too, and we had a room together. My mind was in an awful condition about this time. I felt that I did not want to live, and was afraid to die. A little before Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone were arrested, Miller, my attorney, came back and came to see me, and I never let on to him I had made any confession. He told me he had been to Denver, that he had waited several days in Spokane and they did not send him the money, and he thought best to go and see them. He said Jack Simpkins was keeping close, that they were hard on his trail. I asked him where he was, but he did not tell me, if he knew. He said he got $1,500 from Pettibone, and he said they were all scared, and he said Pettibone told him if he could use his deposition, all right, but that he would not go to Idaho as a witness.

Miller further said he stopped in Salt Lake City and saw Lewis Cutler about the interest in the mining claims at Goldfield, Nev., and Cutler told him he would turn it over to me any time. Miller got me a suit of clothes and some other little articles, and came to see me two or three times before Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone were arrested, and then he put a piece in the paper that he would withdraw from my case and defend the Federation officials. I sent him a letter that that would suit me all right, but he came up to see me after. I did not see him the first time. But he came again and the warden brought him in the hospital to see me, and he said the newspaper report was false, that he had not stated he would withdraw from my case. I told him that I had made other arrangements, and would not require his services any longer.

Mr. McParland came up a few days later and said they wanted me to go to Caldwell before the Grand Jury and give some evidence. So I went to Caldwell before the Grand Jury, and told them the conversation I had had with Moyer, Haywood, and Pettibone in regard to assassinating Mr. Steunenberg, and how I carried out the assassination. I came back then, and about a week later Mr. McParland came up again, and told me I would have to go to Caldwell again and plead to the indictment, or at least to go before the court. He said he would make arrangements and have an attorney there to represent me.

The next day I went to Caldwell, and no one said anything more to me, and when I went into court they read the indictment to me, and I expected Mr. McParland had made arrangements for an attorney to represent me, and that he would answer for me, but no one answered for me, and the judge then asked me if I had counsel, and no one said anything. He asked me then if I wished an attorney, and I told him no, and he said I was entitled to one, and he would appoint Bryant and Cox to represent me, and that I could take the statutory time to plead. Mr. Bryant and I went down in the sheriff's office, but I told him nothing of what I had done. I thought after the confession, as I intended to tell the truth, I was going to plead guilty, but Mr. Bryant told me there were three pleas I could enter, guilty, not guilty, or not plead at all. I told him I would make no plea then, and we went up before the court then, and I told the judge I had no plea to make and he instructed the clerk to enter a plea of not guilty.

I came back to the penitentiary that night, and felt pretty blue, and felt as though I did not have a friend in the world, after Mr. McParland not keeping his word in regard to getting me an attorney, and taking me into court like a dummy, and I not knowing what to say or do. I came back feeling more blue than ever, and, to finish up everything, when I came back that night to the penitentiary, they had my things moved back out of the hospital into a cell, and, as it was pretty cold there, and I was not feeling very well physically and worse mentally, I just broke down again and felt like giving up entirely.

I did not get up the next day, and really contemplated putting myself out of the way, and wrote a letter to my brother and put it between the lining of my vest, and I told Adams if anything happened to me to send this letter to my brother, and that he would find the address on the letter. I think I told him I had something there to put myself out of the way with, but I had nothing in particular only my watch crystal. I was thinking of pounding this or the electric globe up and swallowing it, but I hardly knew what effect it would have. I had heard of people pounding up glass and killing dogs with it, and I had not made up my mind definitely. I was only thinking about it. When I would think of the hereafter, something seemed to say to me not to do it, but there was hope for me, and I would pray, but oh, I had no heart to pray. But I am sure now, that I had dear ones praying for me and God heard their prayers, and kept me from making the last desperate leap into the Great Beyond. I was not very well and the cells were very cold and the warden moved us back in the hospital.

Shortly after this Steve told his wife about my writing this letter, and she told the warden, and Mr. McParland and Governor Gooding came up to see me, and Mr. McParland asked me about it, and told me he understood I had the means of destruction on my person, and that he wanted me to give it to him. I told him what I had thought of, but that I had not thought seriously of it, and that he need have no fear, as I felt better. He talked to me about the hereafter, and that to do or to think of such a thing was awful, and that there was no possible hope then; but said if I would truly and sincerely repent and pray for forgiveness that there was no sin that God would not forgive. He told me he had been praying nearly all day, as he had had word that his nephew, whom he thought a great deal of, had been killed in a wreck near Florence, Col., and had been virtually burned alive. His talk helped me a great deal, and I felt ashamed of myself, and also felt provoked at Adams for telling such a thing; and I don't think that I ever would have carried it out, as I was not sure that it would have killed me, and I had not fully decided to do it. If I had had a gun I believe there were times when I would have ended all.

Soon after this some missionary society in Chicago sent me a Bible, and the deputy brought it in to me, and I felt mean and told him to take it out, as I did not want it, and at the same time I longed for it, but did not want any one to know or see me reading it. I had been trying to pray and ask forgiveness of my many sins, but in a very half-hearted way, and I felt more miserable than ever then, and resolved I would ask for this Bible, but kept putting it off from day to day. At last I asked the warden to bring it in to me, and I began to read it. I was not long reading it through, and I could not find anything in it that said no murderer could enter the kingdom of heaven, and I prayed earnestly for forgiveness, and read and reread the glorious promises, and determined not to give up before I found peace and pardon. True, I was long weeks and months before I found the light or even the dawn, but I kept praying and persevering. I had no thought of turning back; I never doubted God's word and promises, I only doubted because of my own weakness. This peace crept in a little at a time, and I can hardly tell when or how, but I at last began to realize the change, and took great delight in reading the Bible and praying earnestly to God several times a day. I had it in my head I was such a sinner that I had to go through some long lamentation, and the greater the sin, the more God would require of us before He would forgive us.

Mr. McParland had asked me if I would like to have a minister come up and see me, and I told him I would. He asked me if I would like to have Rev. Dean Hinks of the Episcopal Church. He said he had met him, and thought he was a good man, and he came up to see me, and has come occasionally ever since, and has been a great comfort and help to me spiritually. He also brought me several good books that have enlightened me very much, and thank God to-day that I know I am a sinner saved by grace, through no good merits of mine, but all through the blood of Jesus Christ, our blessed Saviour and Redeemer. I do not mean to say that I have all clear sailing, far from it. I have one continual battle to overcome my wicked and deceitful heart, but I praise God that His grace is sufficient.

I thought at first that this was not right, and that God had not forgiven me. These thoughts would arise in my mind, and I thought this had not ought to be. I had no desire to do them, but I would think of them often and try to get them out of my mind, and I praise God they don't arise as much as they used to. But I have found as I read the experience of many noble, good men in the books, in which they give their experience, that Jesus Christ is the only way that we can approach God's throne and plead His mercy, as Jesus is our mediator and redeemer, who took upon Himself our sins. It all seems clear to me now.

I only give this as my experience, hoping that it may help some one if they have or should have a similar struggle. I would not go through such remorse and torment again for all the world. This may seem an exaggeration to some, but it is true, nevertheless. Any one that has had such a struggle and prevailed can readily grasp the truth of my statement.

I will now tell you what I believe saved me. It was the prayers of a dear loving wife, whom I had shamefully and disgracefully left many years before with a darling little baby girl about six months old. As I have related how this came about, I need not repeat here, only to say that when God took away the bitterness out of my heart and let His love shine in, then the former love I had for my wife returned, stronger than ever, if that were possible, and I longed to know if she was alive, or what had become of her and our little baby girl, as my mind was made up then to tell the whole truth regardless of the consequences to myself or anybody else.

I knew I would have to tell my true name, and then all would come out, and I asked Mr. McParland to write to Road Macklon, Brighton, Ontario, Canada, and ask him if he knew anything about Albert E. Horsley or his wife. Mr. McParland wrote to Mr. Macklon, but he was dead, but Mrs. Macklon answered and said that nothing was known of me. I was supposed to have gone West several years before, but that Mrs. Horsley and her daughter lived at Wooler. I then wrote my dear wife and told her the trouble I was in, and asked her to forgive me. I also told her that I had accepted Jesus Christ as my Saviour and found peace at last. I got a letter from her that broke my heart, but only made me cling closer to the Crucified One. She said that she had forgiven me years ago, and had never ceased to pray for me and never would. I will leave the reader to imagine the rest she said to me. I will only say further that there never was a harsh word written in any of her letters, and her dear letters and those of our darling little girl from time to time have been a great source of comfort to me, and they make me cling closer to Jesus, knowing if I never am permitted to meet them here below again, I can meet them up yonder where meeting and parting will be no more, if I am faithful until death, and this makes heaven seem dearer than ever to me.

After I had read my Bible a good deal and felt my sins forgiven, I tried to talk to Steve Adams and his wife to reform and lead a new life, and, although I hardly knew what to say to them as yet, I was somewhat in doubt myself. They had the same answer that so many have, that they intended to, as soon as they got out of that trouble they were going to join the church and live better lives. Steve and his wife lived over in a house in the woman's ward, and I went over there for a time and had my meals with them, and I talked some to them of my experience and determination to lead a new life from this time, and tried to persuade them to do the same. After Steve went to Telluride, Col., with the officers, to locate the bodies of two men who had been murdered there by the Federation leaders, and which Steve had helped to bury, they brought my meals in to me from that time, and I saw Steve only on Saturdays after this, except a time or two when I went over there on Sunday. He came to the men's department on Saturday forenoon while the women took a bath. I never have gone around among the men here much. I usually stayed in my room, or was out walking by myself.

When Steve came in the yard on Saturday, at first he always came up where I was, and we talked together, but all at once he stopped coming around where I was at all, and when he came over in the men's yard, he would stay down in the yard and talk to some of the men. I asked Mr. Whitney if he knew what Steve was offended at, and he said he did not. He had always told me that he was glad that he had told all, and believed we would come out all right, and his wife expressed herself that way, too; but I knew from little things they would say from time to time that they blamed me for telling all and getting them into this trouble, and Mrs. Adams said if she had been here she would have stopped Steve from telling anything, and without them they could never convict Haywood, Moyer, and Pettibone. I never said much back to them at such times, and other times they would say they were glad to have it over with. Mrs. Adams knew about a great many of these crimes, as Steve told her everything.

Steve's brother Joe came later, and also Mary Mahoney, a woman from Telluride, Col., and they sent letters to Steve, and Joe would slip them to Steve when he was visiting him. Steve would show these to the officials here and laugh about them. They were trying to get him to see the Federation lawyers, and told him in these notes that it made no difference what he had told, that they could not use it against him, and that they were his friends and would stand by him. Steve paid no attention to these things at first, but his uncle, Mr. Lillard, who had been here several times to see him, came up and had dinner with them, and the next day or so the Federation lawyers got out a writ of habeas corpus for Steve, and he was released, but immediately arrested and afterward taken to Wallace, Idaho, and charged with the murder of a man by the name of Tyler. He had told me all about killing Tyler and Boule and the others that were with him. Simpkins also told me the same story, and showed me where they killed Boule, when I was up there hunting with him. I know Steve Adams and his wife told the truth in everything that I knew about, though there were many things that he had told me that he had done of which I did not have personal knowledge, but he told them in his confession just the same as he had told me, and I have not the least doubt but what he told the whole truth, and would have stood by it if they had not brought some pressure to bear upon him. What this was I do not know.

NEXT: My Reason For Writing This Book