|

Victor

|

The Labor History of the Cripple Creek District;

A Study in Industrial Evolution

by Benjamin McKie Rastall

pages 20-23

Events Leading Up To The Strike

In August, 1893, H. E. Locke became superintendent of the Isabella mine. The Isabella was at that time working an eight-hour shift—seven and a half hours labor, one-half hour for lunch. Mr. Locke had been managing mines in other districts that worked much longer hours, and wished to lengthen the hours at the Isabella. Accordingly on the 17th of the month a notice was posted to the effect that, beginning with the following Monday, a mine shift would be ten hours, with one hour off for lunch.

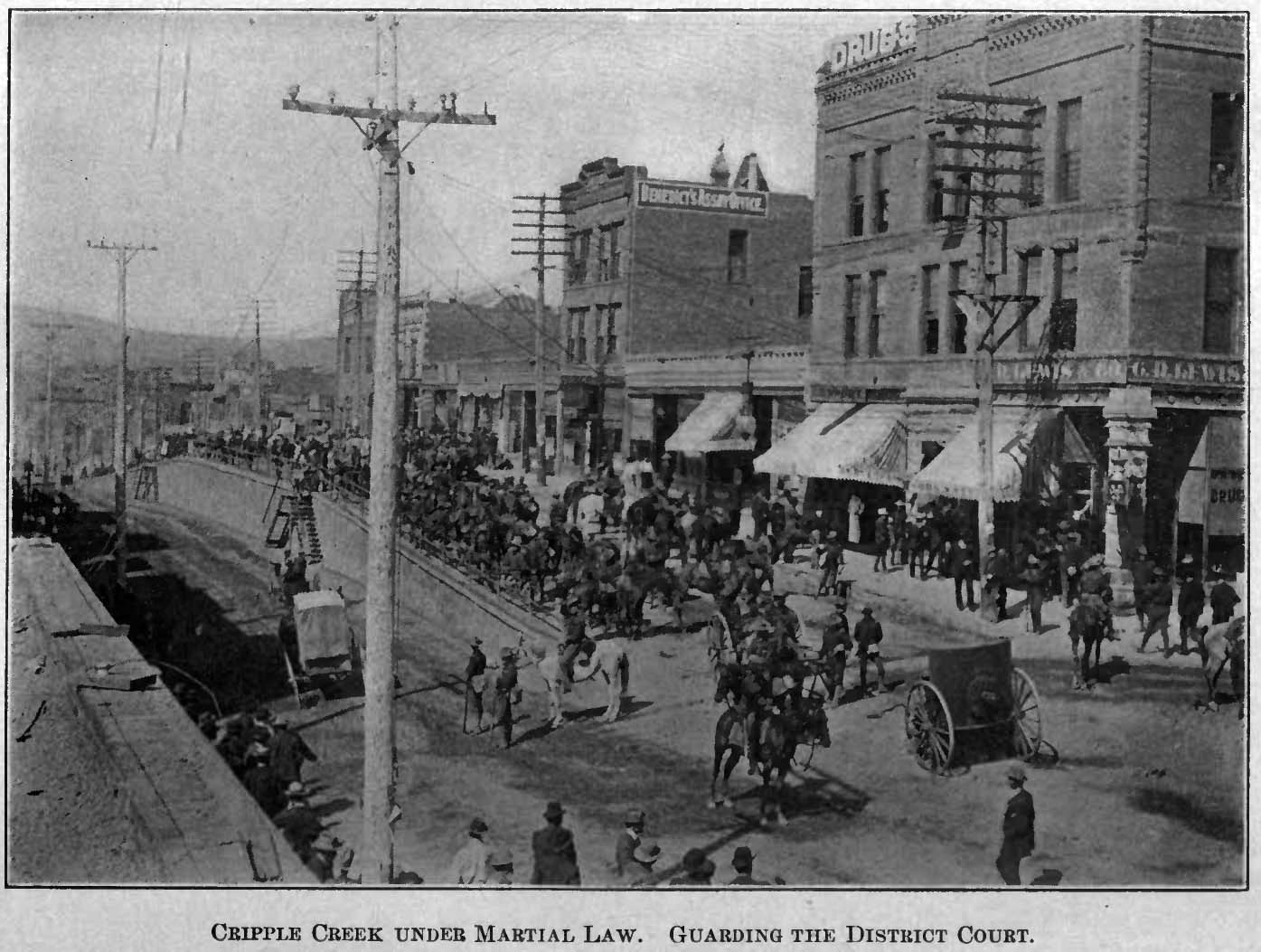

CRIPPLE CREEK UNDER MARTIAL LAW. GUARDING THE DISTRICT COURT.

On Sunday the miners held a meeting at Which they agreed not to submit to the schedule, and when Monday morning came they did not go to work. When Superintendent Locke arrived at the mine the men met him, and a heated controversy ensued, Locke trying to bully the men into going to work, and the men trying to force him to rescind the order. After telephoning to Colorado Springs Mr. Locke concluded to withdraw the order for the time being, and later in the day the men went back to work on the old eight-hour schedule.8

The trouble at the Isabella seemed to arouse both sides to the danger of the situation, and the necessity for prompt action. A committee of miners was appointed to draw up resolutions, and soon after steps were taken to form unions. The Altman Union was the first to organize, and was admitted to the Western Federation of Miners, as Free Coinage Union No. 19, on the 12th of December. Following Altman, unions were formed at Cripple Creek, Victor, and Anaconda, with a total membership on January 1st of about eight hundred. At the time of the strike only Altman Union No. 19 had been admitted to the Federation. To secure authority and uniformity of action all the unions worked under the Altman charter, and the president of Altman Union was executive officer for all the unions of the district.9

So Altman, peopled almost entirely by miners, and located strategically within the mining area, became the center of the union movement and the seat of authority for the organized miners. Colorado Springs, the county seat of El Paso county, was the home of fully three-fourths of the principal mine owners of the district, and naturally became the center of the mine owners' movement. The Cripple Creek District being at that time included in El Paso County, there were thus two centers about which the coming conflict was to develop, Colorado Springs, the seat of county authority and the stronghold of capital, and Altman, the active scene of controversy and the stronghold of labor.

While the unions were organizing, the mine owners were not less active. Frequent conferences were held relative to the establishment of a uniform working day and the question of lengthening hours was constantly agitated among the owners, of eight- or nine-hour mines. Finally, in the early part of January, the owners of the eight-hour mines came together in an agreement to increase the working day at their mines to ten hours, nine hours labor and one hour for lunch. Notices that set forth the agreement, and made February 1st the time for lengthening working hours, were received by the mine managers for posting, about the middle of the month. The appearance of the notices, first at the Pharmacist, then at the Isabella, Victor, and Summit mines, caused considerable stir among the miners.10 Meetings of the unions were called immediately, at which resolutions were passed not to work in mines attempting to lengthen the labor day.

Manager Locke of the Isabella had never been popular with the mining men. He had been the first to conceive the idea of lengthening the working day, and the men now blamed him entirely' for the present movement, and became very bitter against him. Becoming frightened he applied to the sheriff for a guard of deputies, and never appeared without them. In riding to and from the mine he was always preceded by an armed deputy, and followed by another one. This only increased the feeling against him, and a plan was finally made for his capture and eviction from camp.

On the morning of January 20th a large body of men collected in the rear of the Taylor Boarding House, and when Mr. Locke and his deputies came along, they were surrounded, disarmed, and started off on foot down the hill. Arriving at the Spinney Mill near Grassey, Mr. Locke, intimidated by threats, took an oath that he would never return unless permission were given by the miners, and that he would give no information against any one for driving him from the district.11 He was then given his horse, and started off toward Colorado Springs, where his arrival late in the evening produced great excitement. One of the deputies captured with Mr. Locke was a man named Wm. Rabedeau, who will appear several times later in the difficulty.

The miners' unions had already agreed that the men should be called out from all mines that attempted to lengthen the working shift. On January 8th they went a step further and demanded a uniform eight-hour day for the whole district.12 February 7th was set as the date for calling out all men working over eight hours.

The two sides were thus arrayed against each other, the mine owners standing for a ten-hour day, the miners for an eighthour day. In the contest that was to follow the conditions were decidedly favorable to the owners. As we have seen, the country was in the throes of a financial panic, and as far as the labor market was concerned the purchasing power of money had doubled. Thousands of men were unemployed, and willing to work for almost any wage. The mines were generally dry, and would not suffer from a few months' idleness, and there were no expensive plants to depreciate in value by lying idle. Two railroads were being built into camp, and a wait of a short time would simply mean a saving of about three dollars a ton on the transportation of ore. The conditions for the miners were disheartening. Provisions and rents were very high; their unions were but newly formed, only one having a charter from the federation ; there had not been time for the development of a strong unity of feeling, for thorough organization or for the collection of a large treasury fund upon which to draw—things so necessary for strength in a strike. When one reads, then, that the miners won their fight, he will expect to find that extraordinary forces had been acting, and that startling things had happened, nor will he be disappointed.

The key to the explanation is to be found in the character of the men themselves. It must be remembered that Cripple Creek was not the ordinary mining camp, but a newly settled, essentially frontier, district. The men were not of the mining population familiar to the coal fields—foreign born, ignorant, used to obedience, easily cowed—but of the characteristic frontiersman type, come not so much to find work as to seek a fortune. Rough, ready, fearless, used to shifting for themselves; shrewd, full of expedients; reckless, ready to cast everything on a single die; they were not the kind of men to be caught napping, or to be turned from their purpose until every possible resource had been tried. They would act quickly, shrewdly, and effectively; withal straightforwardly, but with small respect for authority, and none too much for law. Nor were the mine owners generally of the usual capitalistic type. The majority of them Were as much frontiersmen as the miners themselves, men who had gained their wealth by successful prospecting, or by lucky buying in the early days of the camp. It was Greek against Greek, similar ideas and strong methods on both sides.

8From the account of Mr. B. W. Pfeiffer, Chairman, Board of County Commissioners of Teller County (1903), who was a miner in the Isabella during 1803. There have been various conflicting stories as to the earlier stirrings of the difficulty. Mr. Pfeiffer's personal observation gives authenticity to his account.

9From John Calderwood's account of the formation of the unions: "Mr. Mcintosh immediately began corresponding with the men at Altman who were taking the lead in forming a union, with the result that a union comprising about 300 miners was instituted in the fall of 1893. Mr. Mcintosh returning to Aspen shortly afterward, appointed myself his deputy, with instructions to organize the remainder of the district, with the result that in less than sixty days I had instituted unions in Cripple Creek, Anaconda and Victor. This achievement, in so thoroughly unionizing the district, was rewarded by a request for me to become president of Altman Miners Union No. 19. I did so. Although four unions had been organized in the district, only one charter had as yet been granted by the Western Federation, that to Altman Union No. 19. Each of the other unions elected a full set of officers, with the exception of president, working under the Altman charter; the president of that union presiding over the remaining unions in the district."

10The notice at the Pharmacist was posted January 17th, and was followed by the others a few days later.

11Accounts by eye witnesses.

12By resolution passed after a speech by President Calderwood strongly urging such action.

NEXT: Attempts at a compromise — The lockout Feb. 1st, 1894 — The strike Feb. 7th — John Calderwood — Preparation by the unions — The injunction of March 14th — Capture of the deputies — Sheriff Bowers calls for militia — Beginning of friction between state and county — Conference between the generals and union officers — Recall of the militia — Compromise at the Independence