|

Victor

|

The Labor History of the Cripple Creek District;

A Study in Industrial Evolution

by Benjamin McKie Rastall

pages 73-78

CHAPTER II

THE COLORADO CITY STRIKE

Smelters and reduction plants are located in Colorado at various centers of population throughout the state. The great bulk of the Cripple Creek ores leave the district to go to these places for reduction. Four plants which handle a considerable part of the shipments are located at Colorado City,—the Telluride Mill, the Portland Mill which handles only the ores of the Portland mine, and the Standard and Colorado Mills, both owned by the Colorado Reduction and Refining Company.1

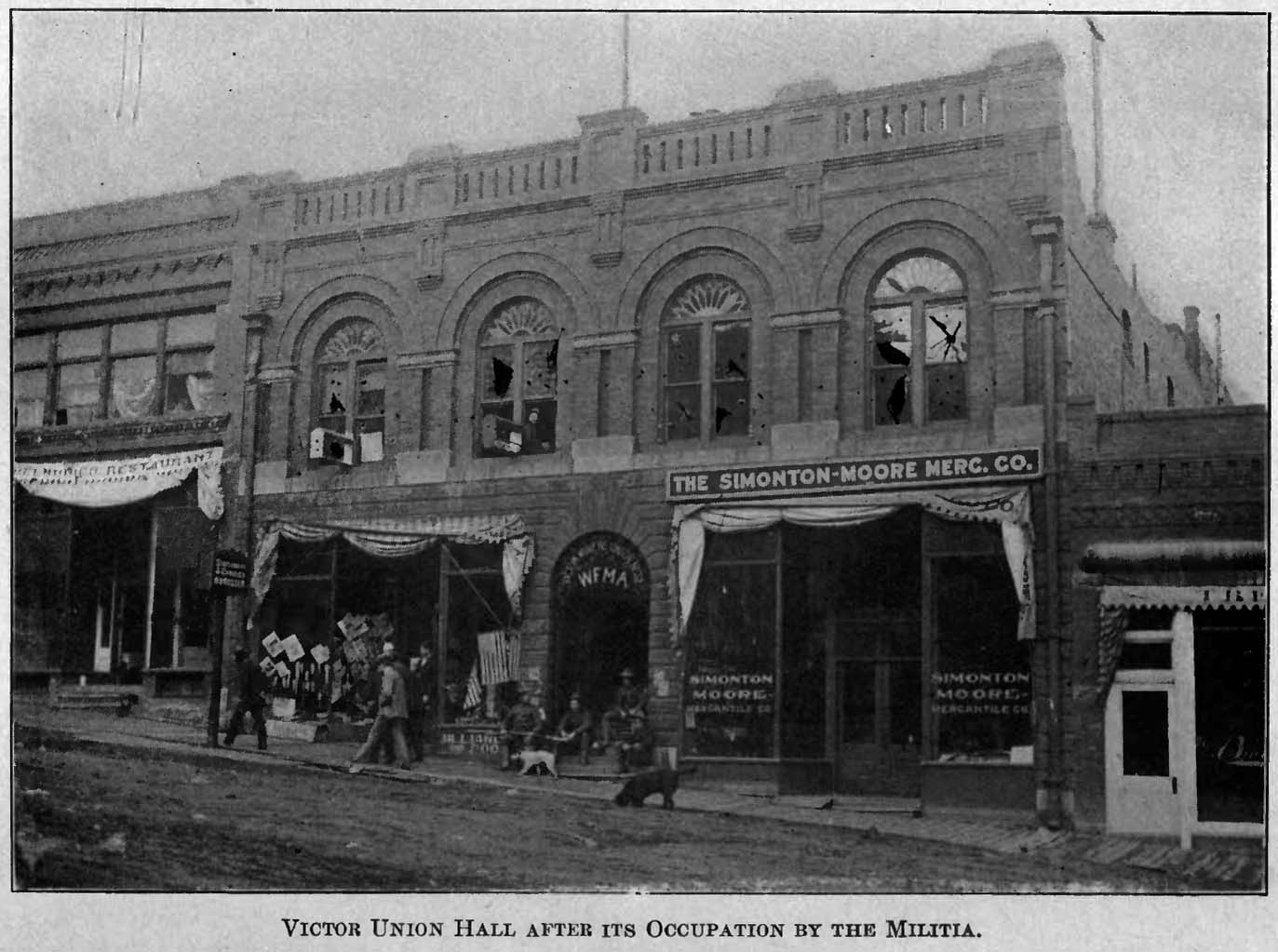

VICTOR UNION HALL AFTER ITS OCCUPATION BY THE MILITIA

The Western Federation of Miners was organized with the intention of including all trades closely allied to the mining industry, and in that idea included mill and smeltermen. No attempt was made to organize the Colorado mills however until 1902, when a general movement was inaugurated to form unions in all the smelters of the state. The movement was unsuccessful except at Colorado City, where Mill and Smeltermens' Union No. 125 was formed in the month of August.2

At Colorado City the union was met from the start by the opposition of the mill managers. It was claimed by the union, and later practically admitted, that men were discharged simply for joining the union, and that as fast as their names became known they were being dropped.3 A. K. Crane, who had become rather influential in the union, was accused of acting the spy, and reporting the names of new members to the company. He was expelled from the union, and later compelled to leave the city. Becoming thoroughly angered, the union determined to make a formal protest against the discrimination, and to back it up if necessary by a strike.4 The opportunity was also to be taken to demand the wage scale in force in the smelters of the mountain towns. This would mean an increase in the minimum wage from $1.80 to $2.25, and slight increases in the pay of men earning between $2.00 and $3.00 per day. The men earning $3.00 and more would not be affected. A protest was also to be made against the deduction from wages of $1.50 per month to cover insurance and doctor's fees.

The committee made its call at the offices of the Standard and Colorado plants on February 14th. Manager MacNeil asked if any member of the committee was in the employ of the Colorado Reduction and Refining Company, and upon the answer being negative refused to meet the committee, or receive any kind of a statement from it. The committee returned to the union headquarters, and a strike was called at the Standard Mill. Two weeks later written demands were presented to the managers of the Portland and Telluride Mills for an increased schedule of wages. The demand was refused, and strikes were called in these plants also.

The opposition of the management had been of sufficient weight to prevent the union from becoming strong in the plants of the Colorado Reduction and Refining Company. Of the 212 men employed at the Standard mill only 46 were union men at the call of the strike. Thirty-six non-union men went out with them, making the total number on strike about 80. Some of the non-union men informed the management that they left their positions through fear of violence, threats of which had been made to them. The Colorado Mill had shut down on February 1st on account of lack of ore, and was still idle on February 14th. The strike accordingly did not affect it, and from its idle ranks the Standard Mill was able to draw workmen to fill some of the vacant places.

At the Portland and Telluride Mills the organization had been more thorough. The Portland succeeded in keeping enough men to run, however, and continued with a greatly reduced force. The Telluride made no attempt to continue, but utilized the temporary shutdown to carry on some constructive and repair work.

Sheriff Gilbert of El Paso County swore in deputies to the final number of 65 to protect the property of the mills. No one was allowed to enter any of them without a written permit from the sheriff or the mill manager. Manager MacNeill himself received a deputy's commission. For a few days until the county could arrange for it, the deputies were paid by the mill managers, and a number of them continued to be so paid. The strikers established a complete line of pickets around each of the mills. Tents and other paraphernalia of camping were provided, and day or night no one entered the mills without having been seen.

A workman's picket never partakes of the nature of a parlor game, nor are the men who can be picked up at short notice to become deputy sheriffs likely to be of a class especially fitted to shine in polite society. There was constant friction between the pickets and deputies; several cases of disorder occurred; and there were charges of brutality on the part of the deputies toward the pickets, and charges of violence on the part of the pickets toward non-union workmen, both of which had more or less foundation in fact.

Manager MacNeill was dissatisfied with the insufficient protection and control of the situation afforded him by the presence of the deputies, and desired state troops to enable him to curb more effectively the activities of the strikers. He accordingly made a demand upon Governor Peabody for troops, but was refused. Mr. MacNeill was able, however, to bring the influence of certain powerful forces in the state to bear upon the governor, and having done so, he proceeded to Denver on March 3rd in his capacity as deputy sheriff, armed with a formal declaration of the existence of a mob from the sheriff of the county.5 As the result of the conference several of the Denver militia companies were ordered to Colorado City.6

There was no apparent necessity for the presence of troops at Colorado City at this time. A mob could not be said to exist in any ordinary sense of the term. Colorado City was quiet except for occasional street brawls, which are common enough there at any time. No destruction of property had occurred, and 65 deputies would seem an ample number to furnish protection for 4 mills. The mayor of the city, the chief of police, and the city attorney united in a protest against the presence of troops.7 Business men protested generally. A petition protest was circulated, received 600 signatures, and was immediately presented to the state legislature.8 There is every reason to suppose that the governor acted under stress in the matter, and contrary to his own personal judgment.

On the evening of March 3rd, 125 members of the National Guard, of whom 25 were officers, left Denver for Colorado City. With them were two gatling guns, 25 horses, and the various equipment for field service.9 Arriving at Colorado City they went into camp. Next morning lines of men were thrown around the mills; the union pickets were forced to disperse; and their camps were removed.10 The militiamen were very vigorous in their actions. The streets of Colorado City were guarded at various times; the uriion hall was put under surveillance; and the homes of suspected union men searched.11 The union's officers were loud in their denunciation of the activity of the militia. Within ten days civil suits had been entered against the militia officers charging them with the arrest, detention, and imprisonment of citizens pursuing lawful vocations, the searching of citizens upon the public highways, the entrance of the homes of citizens, and the seizure and retention of the goods and chattels of citizens.

1The Standard and Colorado Mills are built closely adjoining and are run under one management. It is necessary in various places to speak of them separately, but their close connection should be kept in mind

2Organized Aug. 12, 1902, by Member of the Executive Board, Copeley. Official Proceedings, 1903, p. 26

3Official Proceedings, W. P. M. A., 1903, p. 116. Report of D. C. Copeley

4The eight-hour question was not an element in the strike at Colorado City. The working day in the Colorado City Plants had for several years been eight hours, with the exception only of the sampling departments, where the day was ten hours. Nor was the formation of the union here a part of the general movement inaugurated by the Western Federation of Miners to force the eight-hour day which they had failed to secure by legislation. The Colorado City Union No. 125 was formed in July, 1902, and the legislature which failed to pass the law met in January, 1903, and was in session during the first strike at Colorado City.

5Sheriff Gilbert's communication was as follows:

"I hand you herewith a communication from the Portland Gold Mining Company, operating a reduction plant in Colorado City, and from the United States Reduction and Refining Company, from which I have received requests for protection. I have received like requests from the Telluride Reduction Company. It has been brought to my attention that men have been severely beaten, and there is grave danger of destruction of property. I accordingly notify you of the existence of a mob, and armed bodies of men are patrolling this territory, from which there is danger of commission of felony."

For the testimony of the sheriff later before a special commission, see Official Proceedings, W. F. M. A., pp. 155-159.

Q. "Well, you have testified that you commanded no set of men to disperse. You have testified that you had no warrant for any of these men or that they resisted arrest, and yet you went to the governor and told him that you couli1 not control the situation here?" A. "I went to the governor and told him that I was—it either meant to have men killed there controlling the situation or that we must get men enough here to handle the situation without killing anybody." From testimony before Advisory Board

6"Denver, Colorado, March 3, 1903.

"Executive Order:

"It being made to appear to me by the sheriff of El Faso county and other good and reputable citizens of the town of Colorado City, and of that vicinity in said county, that there is a tumult threatened, and that a body of men acting together, by force with attempt to commit felonies, and to offer violence to persons and property in the town of Colorado City and that vicinity, and by force and violence to break and resist the laws of the State, and that the sheriff of El Faso county is unable to preserve and maintain order and secure obedience to the laws and protect life and property, and secure the citizens of the State in their rights, privileges and safety under the Constitution and laws of the State, in such cases made and provided;

"I therefore direct you, in pursuance of the power and authority vested in me by the Constitution and the laws of the State, to direct the brigadier general commanding the National Guard of the State of Colorado to forthwith order out such troops, to immediately report to the sheriff of El Paso county, as in the judgment of the brigadier general may be necessary to properly assist the sheriff of that county in the enforcement of the laws and Constitution of this State, and in maintaining peace and order.

"Given under my hand and executive seal this third day of March, A. D. 1903.

"James II. Peabody,

"Governor."

"To the Adjutant General, State of Colorado

7Governor Peabody—It is understood that the militia has been ordered to our town. For what purpose we do not know, as there Is no disturbance here of any kind. There has been no disturbance more than a few occasional brawls, since the strike began, and we respectfully protest against an army being placed in our midst. A delegation of business men will call upon you tomorrow, with a formal protest of the citizens of the city.

(Signed) J. T. Faulkner, Mayor.

George G. Birdsall, Chief of Police.

John McCoach, City Attorney.

Chief of Police George G. Birdsall. of Colorado City, in an interview the following day after the arrival of the troops, said:

"I have talked with a number of people during the afternoon, and they are all exceedingly indignant at the thought of having the militia come anions us. If some trouble had arisen which we experienced difficulty in handling, then there might have been some cause for sending soldiers over here, but nothing of the kind has taken place. The assaults have been mainly fist fights, which are apt to take place at any time. I do not know of a place where a gun play has been made within my jurisdiction. If I could foresee that men involved in this labor trouble here would resort to the use of weapons, I might become scared myself, but the boys have never appeared to take that course, nor do I believe that they will countenance such methods in trying to win their flight. They know, as we'd as all good citizens, that they must have the public behind them, and I am sure that they do not care to employ force to win their victory."

8This petition was put into the hands of the officials of the union and circulated to them. See Official Proceedings, W. F. M. A.. 1003, p. 11

9Bureau of Labor Statistics Report. 1003-1904. p. 55

10The union later established some pickets outside the lines of troops

11 For detailed statement of orders, movements, etc., see Adjutant-General Biennial Report, 1003-4, pp. 10 and 11.

NEXT: The Cripple Creek mines requested to cease shipments to Colorado City — The governor visits Colorado City — Conference at Denver — Settlement with Portland and Telluride Mills — Failure of second conference with Manager MacNeill