|

Victor

|

The Labor History of the Cripple Creek District;

A Study in Industrial Evolution

by Benjamin McKie Rastall

pages 53-57

The Position Of The Mine Owners

We saw at the beginning that the Cripple Creek strike was largely the result of a general financial depression, and of irregularity in the employment of labor in a newly-opened mining camp, and that the move which opened the strike was taken by the mine owners.

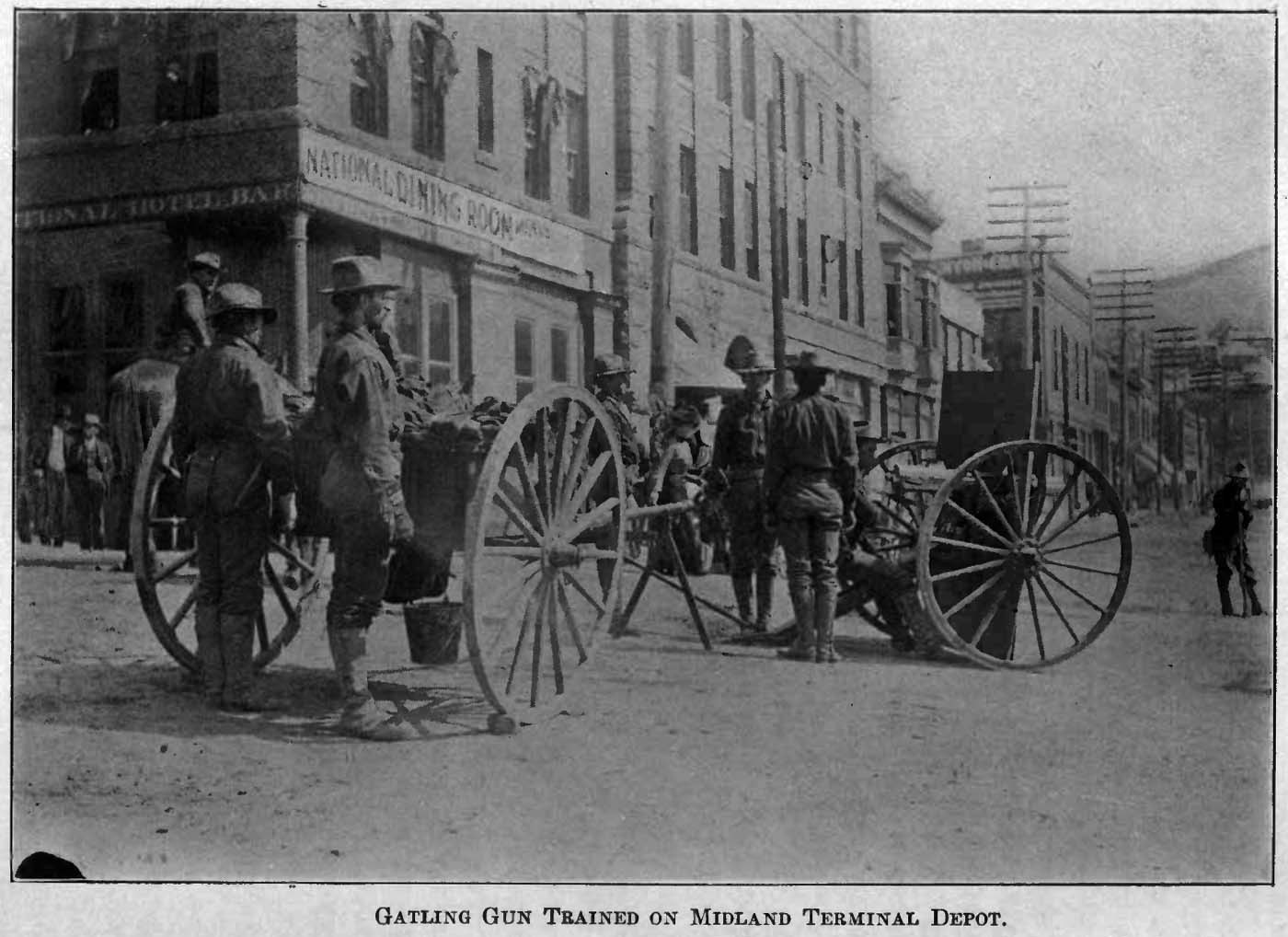

GATLING GUN TRAINED ON MIDLAND TERMINAL DEPOT

The owners felt that under existing conditions they were entitled to a longer working day for the $3.00 wage which they paid, or a smaller wage for the shorter day. They supported their position by pointing to the stringency of the times, the scarcity of money, and the surplus of labor. The logic of business alone, they said, made it impossible to maintain wages anywhere on a prosperous-times basis. They added that they were putting more money into the ground most of the time than they were taking out, few of the mines were paying dividends, and they could not afford to pay such high wages. The mines in other districts worked much longer hours. In Cripple Creek, with freedom from water, mild climate, and pure air, conditions for mining were more favorable than anywhere else, and certainly labor should be no more expensive than elsewhere.2

Feeling that these conditions entirely justified their stand, they refused to accept the various compromises proposed at the opening of the strike, and took no action whatever on the offer of the miners to allow the mines to continue working as they had been doing. Nor did they feel that they could follow Mr. Stratton's example when he opened the Independence on a compromise. They watched with disgust as the miners thwarted attempt after attempt to open the mines, and at last in exasperation made the proposition and demand on the county authorities which resulted in the deputy army.

Later, when the trouble had become so serious that it looked as though hundreds of men would be killed, and a terrible disaster fall upon the county, the more conservative owners began to feel that a small difference in wages was too slight a thing over which to have such a bitter fight. Especially J. J. Hagerman and David H. Moffatt felt that everything possible ought to be conceded to secure a compromise, and ward off such a calamity, and it Was largely through the efforts of these men that the final settlement was effected.

The Position Of The Miners

The miners naturally approached the question from a point of view differing from that of the mine owners. To them the questions of hours and wages were vital points of livelihood. They declared that at the altitude of the Cripple Creek District, varying from nine thousand to eleven thousand feet, men could not healthfully work more than eight hours a day. The strain of such an altitude was so great that many people could not live there at all, to say nothing of working at heavy labor every day for eight hours. The trying conditions due to altitude, they said, were augmented by the nature of mining, in which men had to Work with clothing dampened by water, and breathe foul air and powder smoke. Nor, they insisted, could they live decently on less than a $3.00 wage. Provisions and rents were very high. By the time they had paid $15.00 or $20.00 rent for a miserable little house, bought firewood at $4.50 a cord, water at 5 cents a bucket, and other things in proportion, there was not much left for luxuries. Cripple Creek was a gold camp whose product had not been affected by the general fall in prices, and it was arbitrary to cut their wages just because thousands of other men were out of Work.3

The miners at the beginning wished if possible to make a compromise, and made all the advances along that line. Failing, they settled down to a hard fight, with the feeling that they were justified in going to extremes to keep the mines from opening. The agreement with the Isabella showed them still willing to compromise. Then came the entrance of the deputy army. The rumors in Cripple Creek concerning the deputies were as misleading as the rumors in Colorado Springs concerning the miners. The miners prepared to resist what they understood to be an attack intended to drive them from the county, and emboldened by the sympathy of the governor and his proclamation, held the deputies at bay. Encouraged by their success, and the attitude of the governor, and the fact that the proposals were now coming from the mine owners, they made exhorbitant [sic] demands in the final attempts at arbitration. Fortunately, in making the governor their representative with power of attorney, they left the way open for the final settlement.

The Position Of The Governor

The attitude taken by Governor Waite was in brief that he would do nothing that would aid either the miners or mine owners to win the fight. The militia, he said, should not be called out to win the strike, but simply to preserve the general peace, and should not be used to coerce the miners in any sense of the word.4

In the deputy movement he saw an arrangement, ostensibly by the county authorities, but in reality by the mine owners, meant to force the miners to give up the struggle. This movement, as he. saw it, originated with the mine owners, and was supported by their contributions, and the sheriff was simply a puppet in their hands.

Moreover, in his estimation the assembly of so large a body of deputies was illegal.5 He immediately declared that the sheriff had exceeded his authority, first, in that the right to appoint deputies did not mean the power to form an army, and second, in that he was breaking a state law in appointing deputies from outside El Paso County. The swearing in of men in bodies of several hundred; their equipment with whole stands of newly purchased arms; and their organization into a military body, constituted the formation of an army, and was an usurpation of the power of the governor. In appointing deputies from Denver, Leadville, and other points outside El Paso County the sheriff was disregarding the laws of the state, which expressly directed that a sheriff call aid only from his own county.6 The governor therefore declared the formation of the deputy army illegal, and demanded that it disperse. When the deputies made their forward move he threw the militia between them and the miners, with orders to prevent a conflict at all hazards. And upon the repeated refusal of the deputies to disband, he prepared to call out the whole state reserve.

2Statement by Mr. J. J. Hagerman

3Statement by Mr. John Calderwood.

4From statement by Hon. J. Warner Mills, legal adviser of Governor Waite at the time of the strike.

5cf. Last message of Governor Waite to Legislature Jan. 10, 1895.

6Mills' Annotated Statutes of Colorado, Vol. I, Sec. 856. It shall be the duty of the sheriff and undersheriff and deputies to keep and preserve the peace of their respective counties, and to quiet and suppress all riots, affrays and unlawful assemblages and insurrection, for which purpose, and for the service of process in civil and criminal cases, and in apprehending or securing any person for felony or breach of the peace, they and every coroner and every constable may call to their aid any person or persons of their county as they may deem necessary.

NEXT: The Baleful Influence Of Politics